How to use behavior design to drive change in your team and organization.

Hi everyone, Kevin here.

Following my thoughts on design ownership vs leadership, I thought it would be useful to go further on HOW to create this shared understanding I talked about, especially in environments reluctant to UX or where design is seen as purely cosmetic.

Note that this kind of environment depends on many variables to occurs, and can be a company-scale issue and/or at a much lower level, a team-scale issue. You probably work with this person, either it is a manager or an important stakeholder, who’s use to have strong “design opinions” (or opinions on how the design should be done). He probably drives most of the discussion around his point of view, narrowing any possible debate to a false-dilemma discussion –the “either you’re with me or against me” thinking– leaving no room for sain and user-centered criticisms.

If you feel that at least part of this description fit your situation, well, let me tell you a little truth: you’re part of the issue. As I like to say quite often here, companies and businesses –and the people working there– are full of beliefs. Beliefs that have been built over time, through successes and failures. The belief that, for instance, acting in a certain way will more likely lead to success. Beliefs about how users and customers behave, about what they think, or about how they decide to buy your product. And as social sciences have demonstrated, context influences people thoughts, behaviors, and decisions much (much) more than one would think. Don’t get me wrong: these contextual functional beliefs are not necessarily “bad”.

In fact, beliefs are part of us. Indeed, even tho I can rationalize, doubt, and be critical toward everything, it’s more likely that I will trust you offering me a glass of water being safe to drink. This is because in our day-to-day interactions, questioning everything would require a huge amount of effort. Our brain likes to optimize thing, and beliefs are really effective. These day-to-day beliefs can be classified as a “functional beliefs” –which can be distinguished from “spiritual beliefs” or “symbolic beliefs”, for instance. There is a whole field of study, by the way, for which you can find interesting studies here, here, and there.

Functional beliefs are quite malleable because of their practical nature: ease our thought and decision processes.

“Remember last time you were waiting for the elevator to come? How many times did you press the button to make it come faster?” — an example of a functional belief at play.

Let’s precise that functional beliefs are most of the time based on personal experience, and can be characterized by a tendency to create ad-hoc “explanations” –that are supposed to be easily adjusted by new experiences– and can be shared among a group/population (i.e. stereotypes) which then will become less malleable. Some beliefs have positive impacts and some have negative impacts. The problem in general, however, is that cognitive biases are part of their creation, leading to faulty generalizations and all kind of faulty reasoning.

To Change How People Behaves, Change Their Environment.

All these existing beliefs in organizations predefine how people behave, act, and make decisions. This is called a paradigm. When we want to change a paradigm we often focus on the people. However, as said earlier, the context (or environment) plays a critical role by driving how people behave. In addition, it is less costly –in terms of effort, ability, etc.– to modify people’s immediate context than the people themselves, and, as it is often overlooked, you have greater chances to succeed without people even noticing the “hack”.

In science, the changes you apply to an environment are called independent variables. These variables are the one you have control onto. Note that you probably want to introduce changes in a progressive way to avoid a change-averse reaction: the psychological reactance. As a designer, you probably know this phenomenon typically when introducing a brand new “redesign” of an existing product or feature.

Another concept I want to introduce here is “positive reinforcement loop” or “positive feedback loop”. To put it simply, it’s a process in which, for instance, a specific behavior leads to an outcome perceived as positive, which makes it more likely to occur again. We then say that the behavior is positively reinforced –which doesn’t mean the behavior to be positive per se.

“Predictable behavior leads to predictable outcomes.”

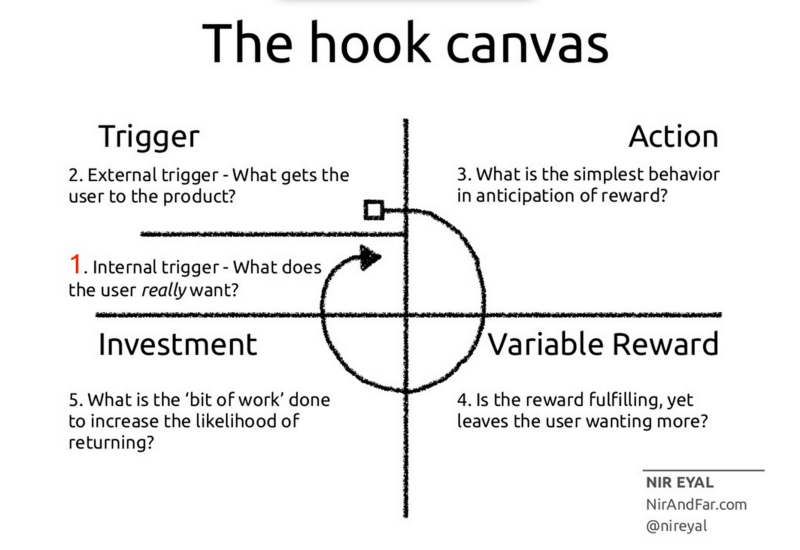

Furthermore, this kind of feedback loop can be provoked and amplified with specific triggers and (psychological) rewards. To give you a sense of how strong this process can be, this is what is known to be the reason for most addictions. On the other hand, this process is used by behavioral designers to incite you to use and reuse an application.

It has been properly theorized, observed, applied and all this shows you that you can not only have an impact but also favorize a specific behavior to make it a new norm. Of course, there is a discrepancy between an experimental environment and reality, and the effectiveness of the tactic will depend on many factors on which you probably don’t have control –unlike in experimental setups. That being said, it doesn’t prevent most of your mobile application to use such process every day with success –even tho they trigger a relatively “simple” behavior.

From Theory To Practice

So we want our team to be more user-centric and keen to try a UX approach. The problem is that we, as UX designers, often feel the importance of advocating for more UX practices at the beginning of a new project/product. That’s understandable as this is a critical phase for user research, etc. Unfortunately, this is also the time at which people will be less keen to hear it if not ready. This can be explained by the high uncertainty and risk level that people’s brain will automatically –and unconsciously– compensate with high change-averse attitude: this is psychological reactance (again).

Instead, people will be more keen to accept change on low-risk/low-uncertainty projects. Pick one project that your PM/PO/Manager considers as “not that important” and plan to apply one UX method on it. You want this method to create a kind of Aha! moment in people’s mind. I personally recommend you to do some User Tests, that has the capacity to show the difference between what people say and what they actually do. If you never practiced such method, I invite you to read the classic “Rocket Surgery Made Easy” by Steve Krug.

And to be honest, as a first attempt to open some eyes on UX, don’t put the stakes too high: if it’s complicated to ask actual users/customers to come at your office perform the test, pick some participants among your colleagues (or other employees). I know, that’s far from being perfect but here the test is more for the observers than the actual quality of data you can gather. Importantly, try to repeat this kind of experiments on small projects as often as possible, and vary the type of methods.

The advantage of doing like this has to do with another interesting psychological effect: people are more keen to accept something they already know. This the confirmation bias. Interestingly, repeated exposition to a new/foreign element (idea, concept, object, etc.) increases psychological safety, playing on our confirmation bias. By exposing people to UX practices, you make them more keen to accept their use. That’s why it’s important to involve the right persons in your experiments.

Also, note the importance of probing for acceptation at the end of your experiments. Ask people what they thought about it, and if they are willing to try it again. Each time, try to increase the value of the experiments by increasing the quality of insights gathered. And don’t forget to show how these insights can drive decisions. Make your team sees you as the facilitator that leads them to more chances of success.

The Tipping Point

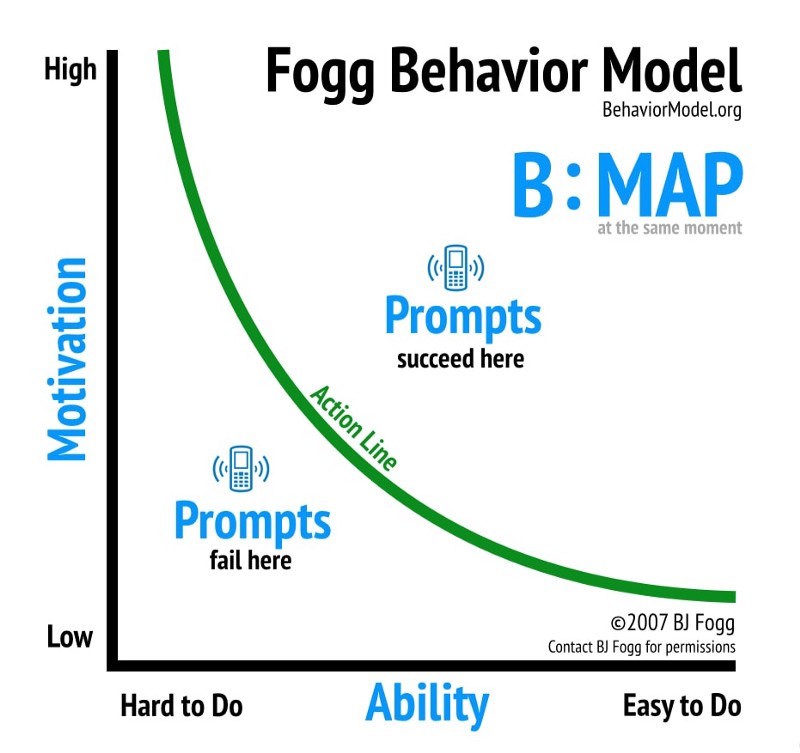

Another element you have to understand about behavior change is the different angles you have to focus on to make it happen. Fogg’s behavior model highlights them really well: B=MAT or Behavior = Motivation+Ability+Trigger.

In other words, if you want a behavior to occur, you need a certain amount of motivation, the ability, and a trigger to perform it. If your motivation is high but your ability is low, you’ll most likely fail to perform it and vice versa. You can read this article which well-summarize the model.

Using the model, we can easily understand that to pass consistently the threshold at which the trigger always succeed you need some prerequisites to be in place. This is the tipping point.

This applies to our case as well, and you have to acknowledge that until these criteria are not properly fulfilled, the change in paradigm will not spread into your organization to become the new norm. And let’s be clear: it can take time.

Notes, limitations, and issues.

If you didn’t notice it yet, this article is about manipulation. This obviously raises some legitimate concerns about the ethical implications of such tactics. Indeed, even tho the purpose here is to better integrate new or disregarded practices –UX methods– and its potential added value and positive impact on a team/company’s outcomes, I can only recommend you to put some clear guidelines to help you take the right decisions about how far you should and should not go to reach your goal.

Remember: this is not about you, nor it is about your career. There are real people lives and well-being at play. You’re not playing god here and you’re not free from mistakes, erroneous judgment, or faulty reasoning. You’re human as much as everyone in your team/organization, with all the bias and limitations. Be humble.

Thanks for reading!

This article was first published on Design & Critical Thinking.

Discussion