Abstract

Design is often weighed down by its own seriousness, bound by the expectations of professionalism, utility, and rigid rationality. But what if we approached design with the irreverence and playfulness of comedy? This essay explores how humor, satire, and irony—exemplified by the absurd automotive experiments of BBC's Top Gear—can serve as tools for inventive and liberating design thinking. By intentionally subverting conventional expectations, comedic design challenges typologies, provokes new ideas, and invites broader participation. It demonstrates how embracing failure with humor fosters resilience and creativity, allowing for designs that are reactionary, engaging, and delightfully unexpected. While comedy carries risks, its ability to disrupt norms and open new possibilities suggests that there is, indeed, utility in tomfoolery.

Utility in Tomfoolery

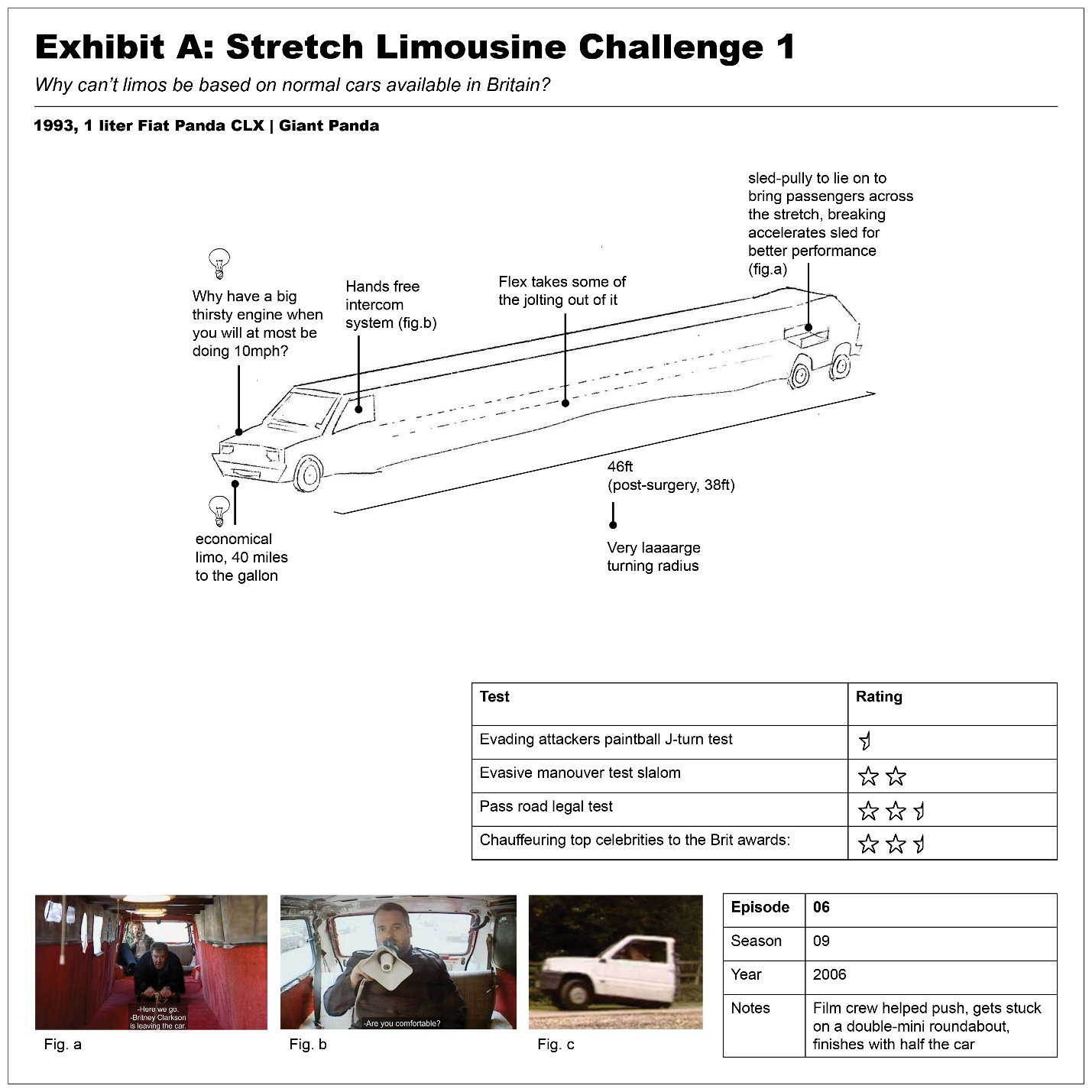

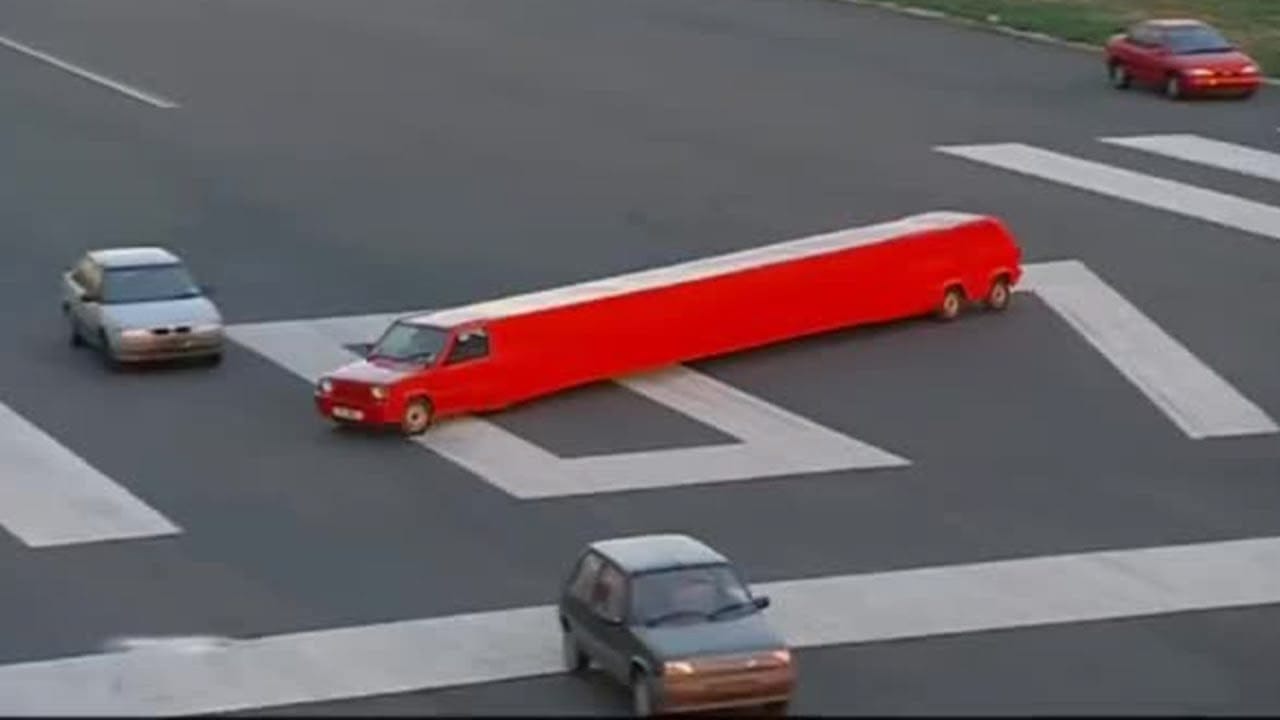

You see a car-shaped object on the horizon, approaching (Exhibit A). As it begins to configure in your vision you discern a regular Fiat Panda appear with its classic boxy nose, painted a bright red. Its body begins to follow, but with each second it elongates as if being elastically stretched right out of a cartoon, revealing more and more bright red bodywork. A staggering 46ft later, the back of the car finally appears, pulling a straggling extra pair of wheels for support, still bowing like an exaggerated Dachshund. This is no small Panda… it is a ‘giant Panda!!’ its creator, Jeremy Clarkson fondly exclaims with a self-indulgent grin to his open-mouthed colleague, Richard Hammond.

Clarkson’s stretch limousine Panda is one of the many monstrous forms of automotive vehicles television show BBC’s Top Gear has created over the years. It is a result of the three presenters Clarkson, Hammond and James May, responding to a "How Hard Can It Be?" Challenge, a contrived real-world scenario that demands a fresh re-invention or application of the car. In this episode, the presenters insightfully recognized that all current limousines available in the market were specialized production vehicles and were only American made. Asking, “Why are limos not made from normal, cheaply available cars in Britain?” the three hit the drawing board with ideas.

This type of questioning may seem familiar to you because at its core, it is a kind of design challenge. The three unearth a gap or a problem faced by consumers and set about engineering a solution. They mull over, they prototype, and they test. However, as their objective is to entertain, every design decision they make is a carefully calculated gag to incite the greatest amount of laughter from their bemused studio audience. In a perfect performance of irony and physical comedy, the giant Panda elicits a booming guffaw from its very first appearance on screen.

Free from the entanglement of mundane designer obligations (such as the serious business of functionality, progress, profitability, safety and replicability), they create designs that almost never work. However, by deliberately operating against these forces of the (boring) real world, they are able to think differently to the most extreme and wondrously so.

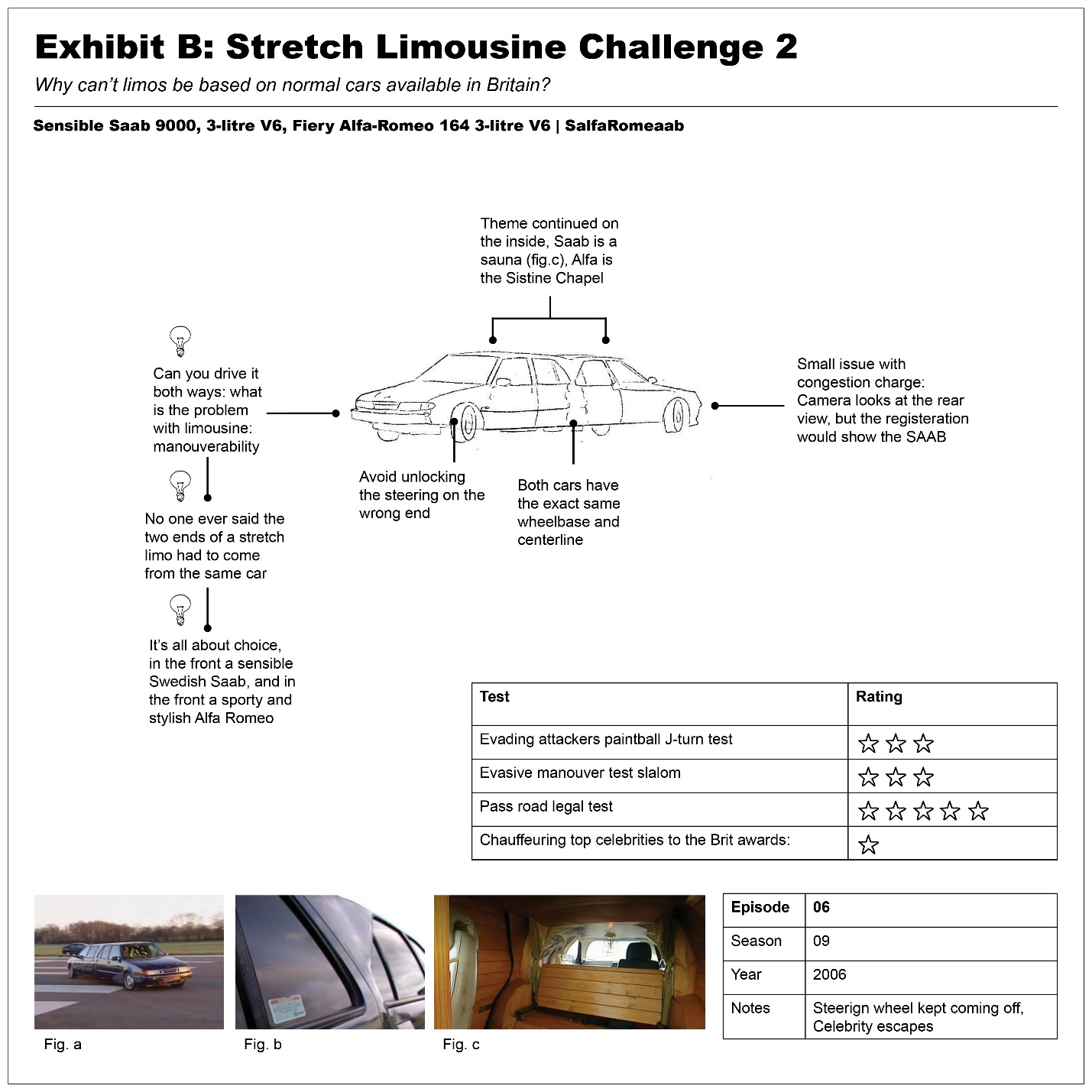

In the same episode James May illustrates this unique ingenuity, solving the Challenge by stitching two front ends of different cars into each other (Exhibit B). He pitches his Frankenstein project, an Alfa Romeo and Saab joined at the waist, as being able to solve the thorniest problem with limousines, their maneuverability. If stuck, simply walk out of one driver’s seat into the one facing the other direction and drive away. With a salesman-like swagger, he persuasively describes how the SalfaRomeeab is all about choice, giving users a two for one, a sensible Swedish Saab or a Fiery Italian Alfa at your service.

Are these ideas ridiculous? Yes. But are they also intriguing? Absolutely. In order to decipher why, we can sift through their teasing and unearth an interrogation of design typology. Cars are supposed to be a certain way, looking and behaving as we have grown to expect after decades of design evolution. But Top Gear, through its infectious shenanigans, has the courage to ask maybe those ideas may not be so inflexible or fundamental. I argue that within the comedy, dare I say it, is a power of liberated lateral thinking that simmers beneath the surface.

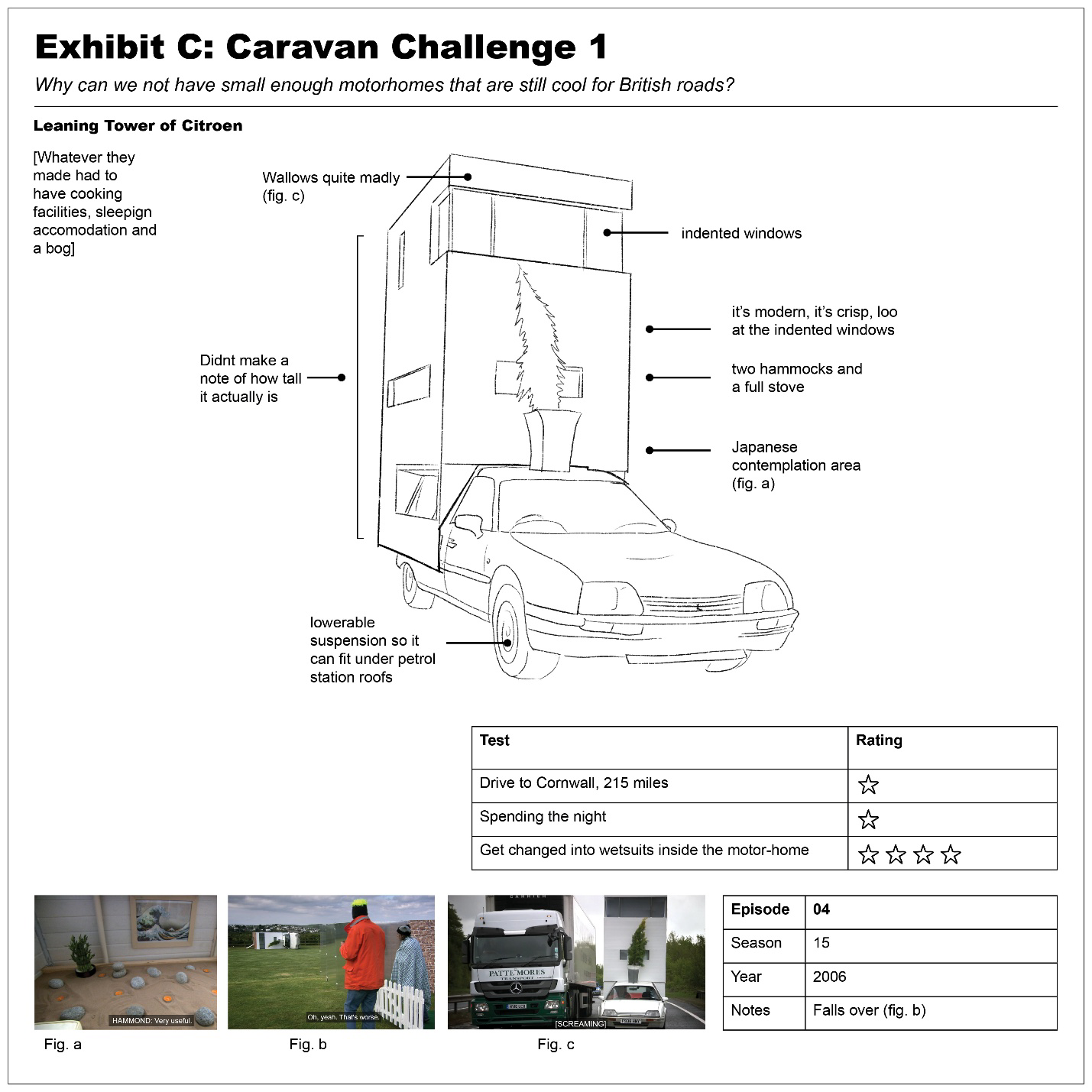

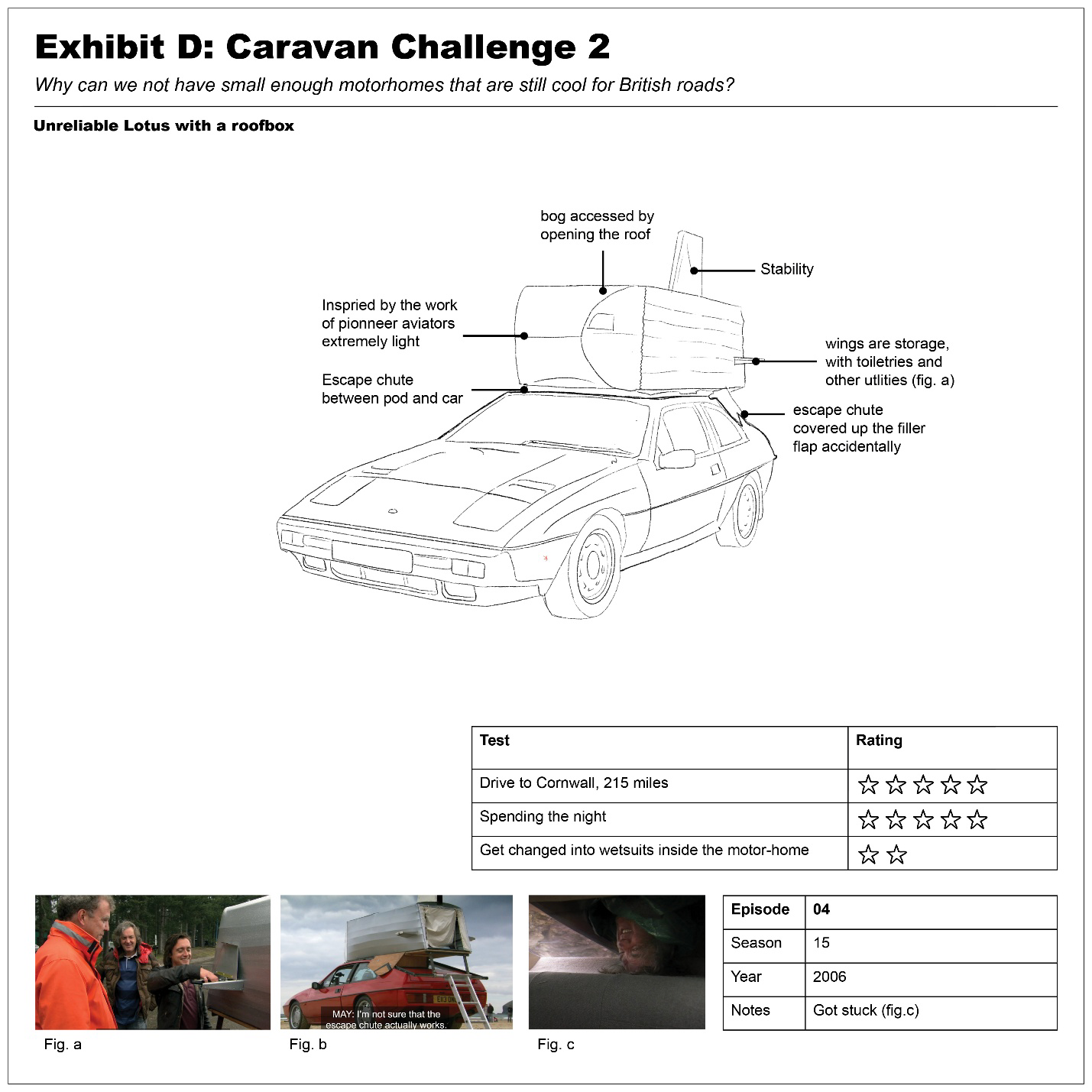

Exhibit C & D: Caravan Challenge 1 & 2, Exhibit E: Ambulance Challenge 1, Exhibit F: The World's First Convertible People Carrier

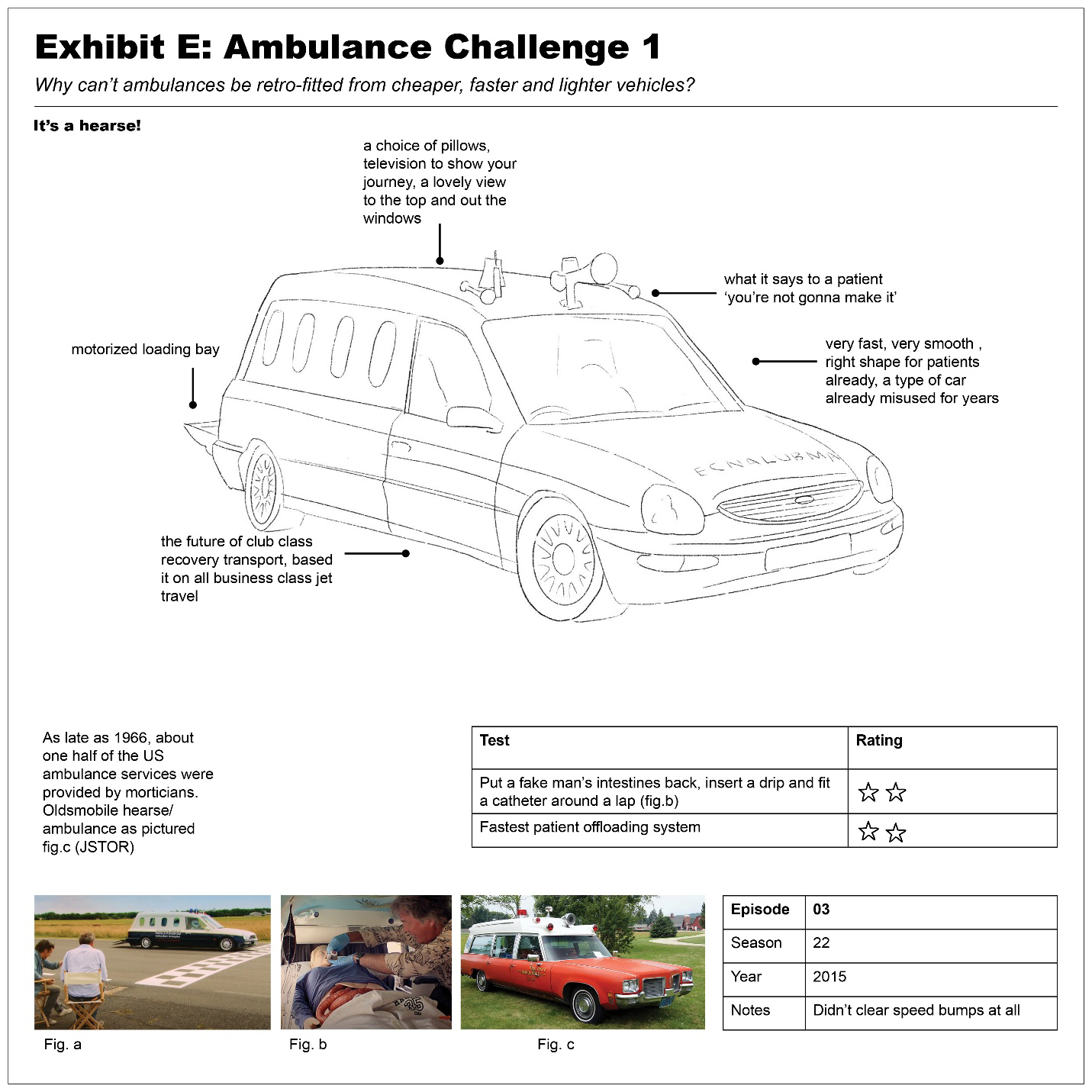

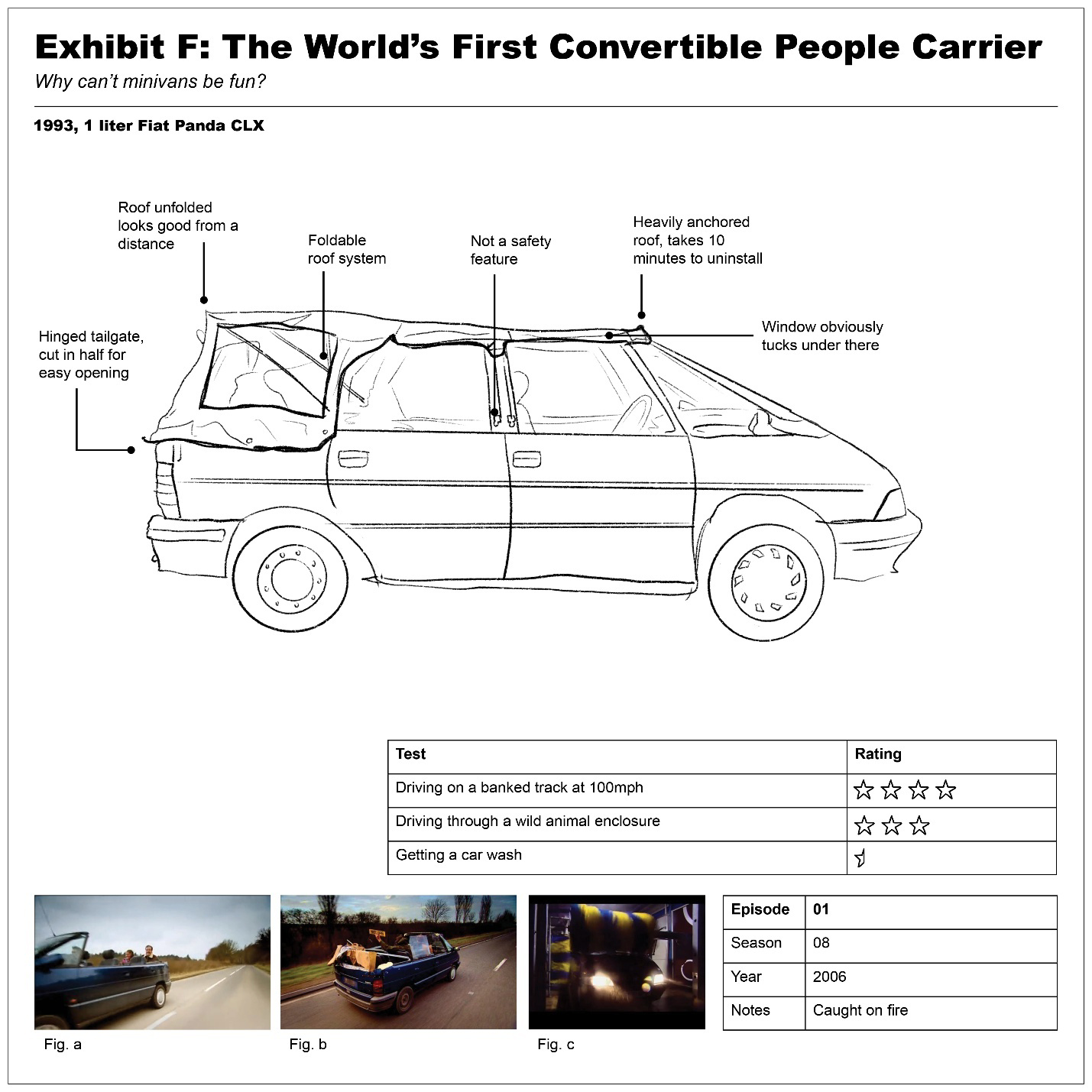

Tell me, why can’t caravans be modern, sleek and lightweight (Exhibits C & D)? Why can’t ambulances be retrofitted from hearses (Exhibit E)? Why can’t mini vans be convertibles (Exhibit F)?

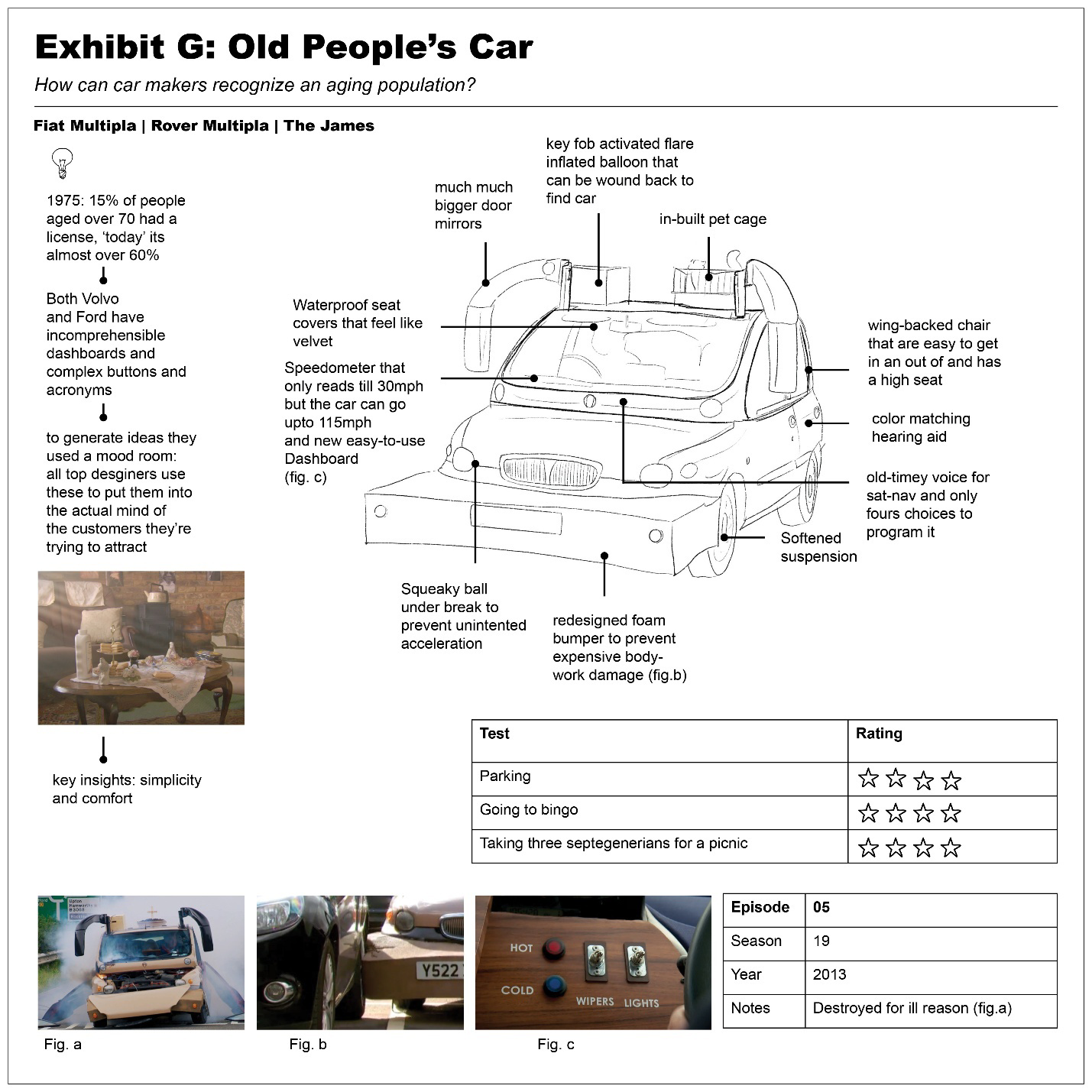

Many of these ideas arise from a respectable amount of market research. In one episode, Clarkson sits in a Ford and then in a Volvo, flabbergasted at the degree of technical proficiency required to operate their dashboards. Staring at the abundance of buttons, screens and obscure acronyms, he worries about the 60% of the population of licensed drivers being over the age of 70, making the point that standard cars were not designed with aging in mind at all. So of course, they needed to make an ‘old person car’ (Exhibit G) and of course it was painted brown with exaggerated door mirrors, high wingback chairs and a pet cage on the roof.

But ideas that emerged about the car communicating its location and a simplified GPS interface and dashboard were undeniably compelling. It is clear that even though funny ideas are welcome, there is no excuse for arbitrariness (even the shade of brown was chosen to match a hearing aid). For the jokes to land, each needed to be tied to context whether in the studio or in real life, also strangely resulting in generative and applicable design.

The ‘old person car’ does explode when the episode completes, and many of their creations do die horrific, fiery ends. But failure is also a very familiar experience in design, though we aren’t taught to laugh at it. We are destined to publicly embarrass ourselves as our professions claim we have a perfect grasp of the world even though we often fall short. Instead of fearing failure, what if we embraced comedic enterprise as a way of giving our fledgling ideas a chance of growing into something more profound and meaningful. By failing humorously instead, we maintain a healthy distance from our work, giving us much needed resilience in the face of challenges and an excuse to turn away from our pretentions.

Furthermore, if everyone was in on the joke, maybe people would be more inclined to participate and contribute (who could resist?). This is design that is meant to be reactionary, pulling people in instead of lulling reviewers into acquiescence, grabbing the precious dwindling resource that is our attention. With this type of design, we learn how to embrace the absurd and satirical, constructing an entirely different relationship to our audience, one that is enchanted with the dust of the sparkling creativity of entertainment television.

It is important to note that this is a fierce but also tricky power to wield and no one else but Top Gear can better illustrate its ability to decline into reprehensible offense. If you knew anything about the show before reading this article it would be their controversies, and I do not wish to condone or hide any of it. Indeed, there is a very detailed Wikipedia page listing their every offense as their comedy veers off into cheap discriminatory gags. But I wonder, at the risk of sounding (ironically) cliché, if this power could be used for good, if we could learn how to design without settling for what is familiar, bottlenecked to well-trodden paths of forgettable ordinariness.

I think what I am trying to say is perhaps if we took things less seriously maybe we would design more inventively, that there is utility in the tomfoolery. Let us shrug meeting the expectations of a singular sense of rightness prescribed by our task masters and instead embrace difference.

As I write the ending of this spiel, I am reminded of my peer in architecture design school scorned in review for her abundant use of triangles. Shock and horror ensued at the lack of orthogonality, her critics arguing that there was no meaning, no visible rationality to her decisions. She later confessed to me that she thought the functionality of 90-degrees was overrated and isosceles triangles made her project more amusing to resolve. In my unacknowledged admiration of her (me appreciate triangles as a sophomore? Never) I wonder why I had such little ability to question or rebel against conformity and dogma, and now I know I just needed to find my sense of humor.

References

- JSTOR, When Ambulances Were Hearses https://daily.jstor.org/when-ambulances-were-hearses/

- Wikipedia, Top Gear controversies https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Top_Gear_controversies

Written by Ami Mehta.

Ami Mehta is a design researcher and 3D artist exploring the intersections of critical design, and material culture. By day, Ami creates research tools to build community relationships and by night she designs immersive digital experiments that bring stories to life.

Links

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ami-d-mehta/

- Website: https://www.amidmehta.com/

Discussion