How our narrative around innovation echoes our perception of time and the way we act towards complex challenges

Hi, Kevin here.

I recently stubble upon a personal reflection that made me think about what I do and –ultimately– how we tell the story of our actions as a society. It’s not like a big revelation or something, but rather a subtle yet important underlying structure of our main narrative that I find interesting and wanted to share with you.

A few days ago, I was listening to a conference (in french) in which Étienne Klein, a French physicist and science philosopher gave a very interesting lecture on the role and importance of sciences in society.

From “Progress” to “Innovation”

Among all the very interesting points he makes and develops, E. Klein speaks about the rise and omnipresence of the term “innovation” not only in business but politics and society in general over the last 20 years, which replaced the notion of “progress”.

Here is a rather long –but worthwhile– excerpt of the video I translated in English for your convenience (emphasis mine) I invite you to read to the end:

[The] new technologies by the perspectives they bring to light, by the upheavals that they make possible, by the globality of the questions that they pose while bypassing the technical aspects, they end up being linked to the question of values and this is when the subject becomes political.Back in time, it was not [political], in a way, because the activity of the researcher –or of science in general– was embedded in the idea of “progress”. And therefore science being considered as the “engine of progress”, all the advances that it allows are interesting, must be exploited, even if it means going back if the effects they produce do not please us.

But as you well know, the word “progress” has disappeared from public discourse. [With a colleague, Gérald Bronner] we looked in public speeches how the word “progress” has declined throughout history and what we see very clearly is that the word has disappeared. It has been used for three centuries with a capital letter “P”. It lost its capital letter after World War II, and it began to decline at the end of the 1980s, when a very old word –which was abandoned– reappeared in the French language: “innovation”.

The curve of the term “progress” (which decreases) intersects the curve of the term “innovation” (which rises) in 2003, and the word “progress” will completely disappear during the French presidential mandate of 2007–2012 (Nicolas Sarkozy) […] There is something absolutely dizzying about this, as a word which has been so structuring to modernity for three centuries has been erased.

So we could say “it’s okay, ‘innovation’ and ‘progress’ are two synonymous words so we simply modernized our progressive discourse by replacing the word ‘progress’ with the word ‘innovation’” [… ] but if we look at history from that of the enlightenment, the rhetoric in which the word “progress” find its meaning and we compare it to the current rhetoric of “innovation” we realize very easily that our way to talk about innovation does not do justice to the idea of progress. One could even defend the idea that our discourse about innovation –not innovation itself– contradicts the very idea of progress.

The idea of progress consists in accepting to sacrifice some personal present in the name of a collective future, as Kant explains in his book “What Is Enlightenment?”. This means that you have to configure the future in a credible and attractive way, long in advance, and then work to bring about this new world that you have envisioned.

It must be credible because progress is not the belief in utopia. It’s not about inventing another world, it’s about thinking about a different but accessible world, with a path that will allow it to be built –and it is science that gives credibility to the futurist discourse. It must be attractive because “progress is not automatic” and therefore we must work to make it happen.

Kant brilliantly said “progress is a doubly consoling and sacrificial idea: it consoles us for the misfortunes of the present since our children will live better, and it consoles us for the sacrifices that it imposes on us because it gives them meaning.” So the idea of progress is based exclusively on a concept of “passing time” which is constructive: time is our ally, it is the accomplice of our freedom and our will.

Now take “innovation”, […] the word appears in the 14th century as “low Latin” in legal vocabulary. What we called an “innovation” at the time is what we would now call an amendment to a contract: you have signed a contract, something changes in the periphery of the contract, so you make an amendment so the contract remains valid. That is to say that innovation, in this context, is what must be done so that nothing changes.

Later, the word circulates in other disciplines, notably in politics: you find it in the prince of Machiavelli. Machiavelli explains that “the prince must not innovate politically when he has power unless his power is threatened”. Once again, innovation is legitimized by the fact that it must allow nothing to change. Then, for the first time the term is used in a technical context by the English philosopher Francis Bacon, who published in 1625 a book called “Essays, or, Counsels civil and moral” in which there is a chapter called “innovation”.

When I give it to my students to read without telling them who wrote it or when it was written, everyone thinks it was written last week, because in 2021 we are talking about innovation like Francis Bacon –which is a bad sign because Francis Bacon was not a philosopher of enlightenment.

[F. Bacon] says that “passing time is corrupting, time degrades situations. What to do to prevent the evil from winning? Innovate. Not too fast, because if the innovation is too fast it will be welcomed as an outsider by the population; not too slowly because if we innovate too slowly the damage produced by the passage of time will become irreparable; and therefore we must innovate at the pace of time”.

Interestingly, if you read the text written by the European Union in 2010, it was a question of making the European Union “the union of innovation”, replacing the Treaty of Lisbon which aimed to make the European Union “the society of knowledge”. We have moved from the “society of knowledge” to the “union of innovation”! So, here you have a 50-page document in which the word innovation is cited 300 time without being defined anywhere. [Innovation] has become a “totem word”.

The first page of this text reads: “Europe has understood that it is facing challenges whose severity increases with the passage of time […] and Europe has understood that it will be able to meet these challenges only through innovation.” This is a plagiarism of F. Bacon, that is to say that this is the critical state of the present which justifies the innovation and not a certain idea of the future that one would configure in advance in a credible and attractive way. And this upheaval certainly plays a role in how technology is discussed in society, and especially at the political level.

New technologies are linked to the question of values, and no longer to the question of principles. Before, it was on principle that we carried out innovation -without naming it by the way- by principle of progress. Today, it is a question of “value”, but the value of a value is less universal than the value of a principle, since it depends on the evaluators: all values do not have the same values, everyone has their values. And so the discussions never converge because there is no transcendent principle that can lead to an authoritative decision.

Technologies in public debates questions our idea of society, of what it should or should not become, and also our way of working, of spending our time, of being touch with others and with our environment, on the basis that it is up to citizens to examine the type of companionship they wish to build with new technologies.

Progress as a positive, desirable future-state

Although we can criticise this position as an appeal to a more traditional view of change, one that seems to appeal to traditional planning and command & control, I don’t think it is necessarily the case here. Moreover, I appreciate the historical evolution of innovation & progress and their relationship to our perception of time, and ultimately to our perception of our societies.

Personally, I tend to think that, more often than not and despite our good intentions, innovation is employed for the very reason described by E. Klein, that is to say, “to not change anything”. But whether we agree or not that innovation sees “time as corrupting” and therefore seeks status-quo or whether we should use the concept of “progress” instead, I think we can agree that whatever the word we use, we tend to seek positive changes through our actions.

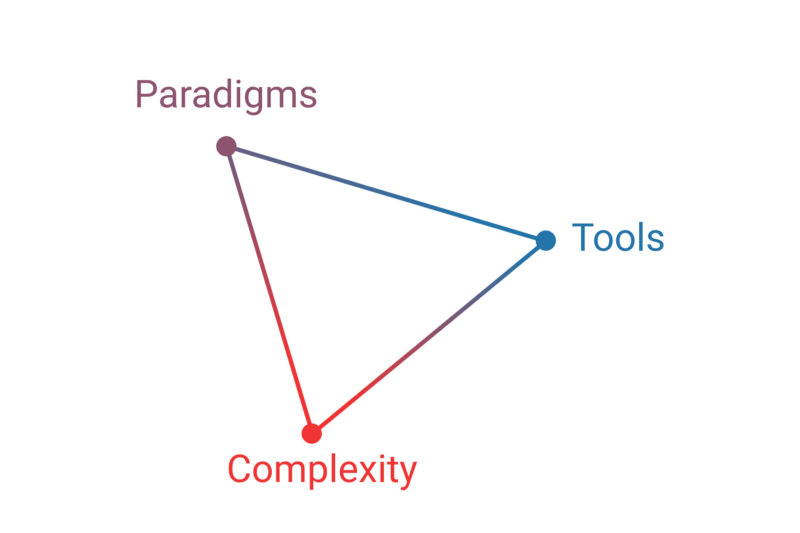

Now, as I mentioned in previous articles, there is a (non-causal) link between how we approach the world (our paradigms), the complexity we are facing (the context), and the tools we use. Thus, I think this is worth questioning and thinking about “how we do what we do”.

Coincidentally, my definition of “innovation” so far match pretty well with this idea of “progress”:

Innovation: “Significant positive impacts/changes in the context we are acting in.”

Now, one might ask: is innovation always positive, if it has negative outcomes for the wider community, can we still call it “innovation”?

And I think this is a very good and valid question. Given E. Klein definition, only progress is positive because it implies working towards an achievable common ideal.

Given my definition, “significant positive impacts/changes in the context we are acting in” –which is, to me, a “should” (prescriptive, not descriptive) as to “what we (as a group) should see in order to categorise it as such”– then by definition something that has significant negative impacts to a wider community should not be categorised as an innovation.

This definition also implies a “set of causes & effects” (or “interactions”) rather than a single-point solution (eg. not “the iPhone is an innovation”).

So innovation is a process, right?

Yes, we can probably frame it this way.

Or perhaps, because of how it is used today and what we generally associate it with, there is value to take some distance between the process and the persons that perform it. “Doing innovation” and “being innovators” flatter our egos. Instead, I would say there is no “innovation in the present” but rather “innovation is a realisation with the benefit of hindsight”.

In other words, something that happened and that we can only observe now, something of the past that we benefit from in the present and that help shape our future.

And you, what are you’re thoughts?

Anyway, thanks for reading!

Discussion