Hi everyone, Kevin here.

It's been sometimes since the last update. After the State of Design 2025 and all the surrounding activity, a much-needed break was necessary. This community has always been like this, oscillations between fast and then slow punctuate its life.

Talking about oscillations, spring is definitely here. I've always felt nature wears green way better than grey, and longer daylight definitely changes our internal rhythm. As someone who cycles at least 80 km (about 50 miles) a week –and who considers my bike as a mode of transport– I can tell the impact of both longer days (more daylight) and a greener environment has on my cycle experience.

Note that this is also something you regain as soon as you bike almost every day, whatever the weather or time of year, is spatial and sensorial awareness of travel. Subtle changes are noticeable; the composition of the space, its disposition, aesthetic and infrastructural underlayer become evident. It makes you think and feel in space and context.

Anyway, coming back to the update.

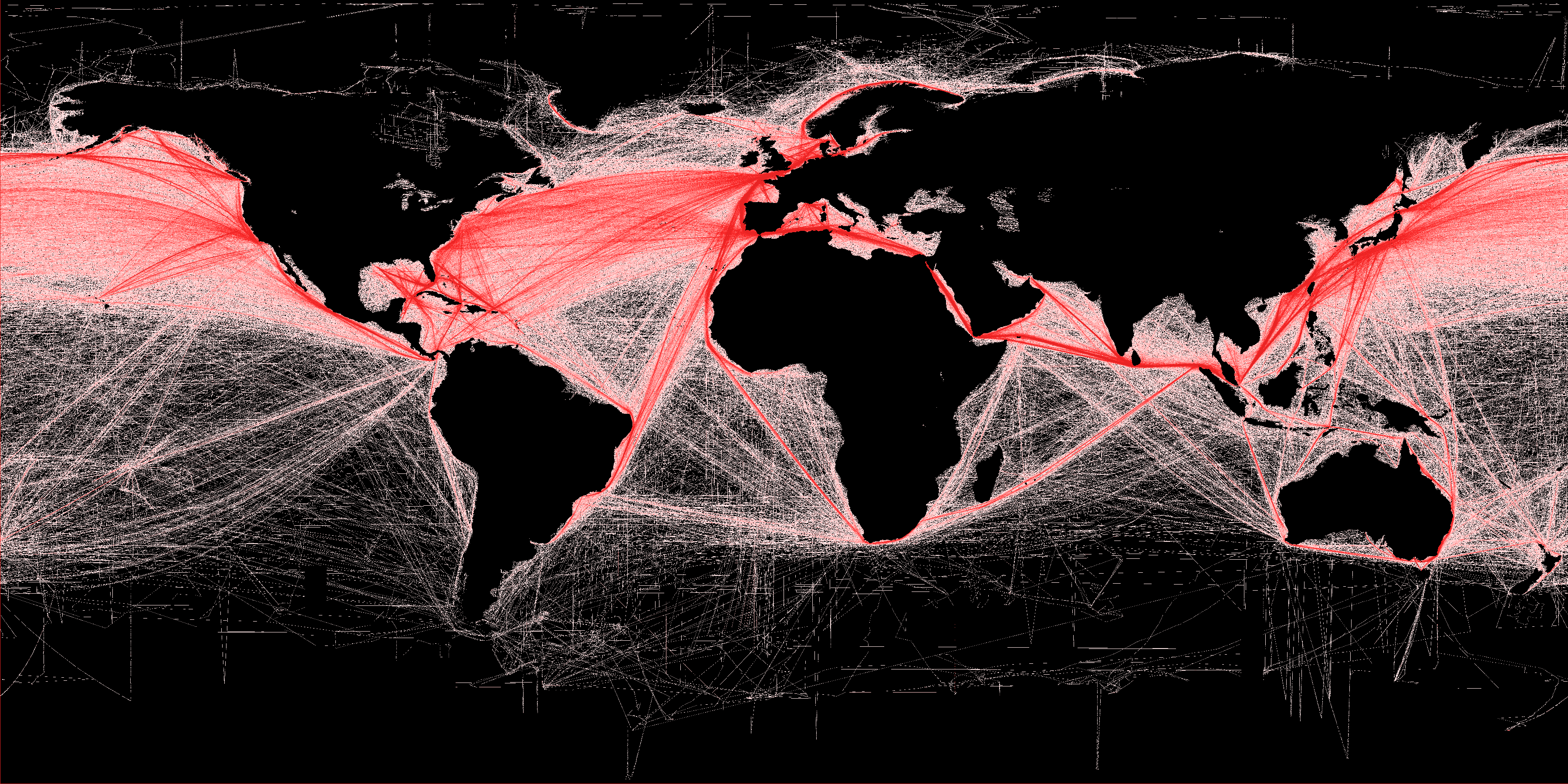

New channel: topic-geopolitical, because we need to engage with the discourse more than ever.

If you are part of the community on Slack (if not, join us here), you might have noticed our new channel #topic-geopolitical. If the past few months have shown something is that everything is interconnected. Designers, makers and innovators alike need to engage with political discourse and its impacts, not only to make sense of it, but because it is a substrate that shapes and is shaped by the social.

If design and designers aim to make any kind of meaningful change in the world (which they claim to do), it has to actively engage with what composes our world, which is deeply social.

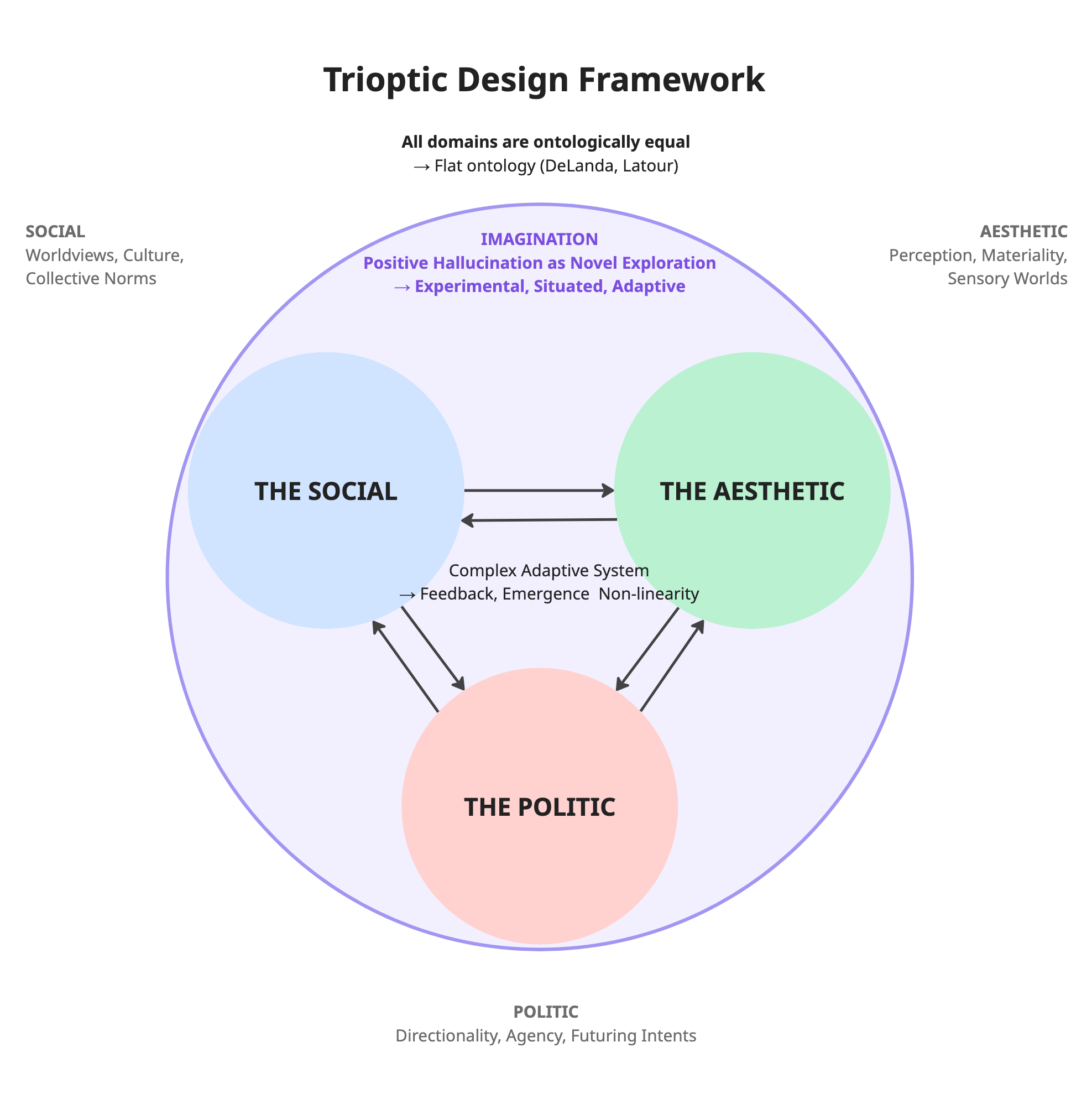

Exploring the trioptic design framework

This is an excellent segway to my ongoing work in expanding my social design and New materialism exploration. The notion of social design was always incomplete, and this new exploration tries to articulate a framework or scaffolding for the kind of design (and designers) we need right now, a trioptic design approach: the social, the aesthetic, the politic.

The trioptic design dimensions:

- the social make sense of the worldviews in a landscape;

- the aesthetic articulates the mediums;

- the politic enacts an intent about the future.

I believe there is also a claim behind this exploration: Design is not neutral, and the designers even less.

The aesthetics of the mediums we interact with are codependent on the message they convey. It uses social languages that support certain ideas, or sometimes, subvert them. The message is politic, in the sense that it enforces a worldview, a directionality, an intent, about how the world should be.

Beyond the shared belief that design is (and the designers themselves are) apolitical, that it/they just “serve the users”, I think there is simply a real aversion to discussing politic and a total misunderstanding of what is aesthetic.

To that, I'd argue:

- Design is political not just because of its effects, but because of its very nature as a practice of world-shaping. As Carl DiSalvo writes [1], design can act as a form of prefigurative politics—a way of giving material form to values, institutions, and ways of living that do not yet exist, but could.

- Design is aesthetic because it articulates a concept which conveys a message; design materializes ideologies. As Tony Fry writes [2], design is not only a material act but an ontological one.

Politic is also a better dimension than ethic, first because it embeds the latter, and second because it moves back the discussion to intent and directionality rather than focusing on the (illusion of) certainty of the outcome. After all, the quality of your ethic is very much dependent on your ability/power to change the world around you.

While I'm still in the process of articulating properly the approach, I think we can take an example to elaborate a bit its central thesis.

This post by Josh Lovejoy is an interesting case. To simplify Lovejoy's core argument:

Effortlessness, seamlessness, and productivity are not inherently human-centered design goals.

Or in other words:

- Effort can be meaningful

- Seams can create connections

- Productivity is hollow without fulfilment

First, and contrary to what is said in the post, I think there is reasonable evidence to suggest UCD, HCD and UX design are limited frameworks, as first and foremost productivity-focused frameworks in techno-solutionist paradigm(s) –which, in most cases, serves techno-feudalist interests.

I think there is less value in trying to redefine these frameworks account for their gap, than trying to bring a third perspective to the case using a trioptic design approach:

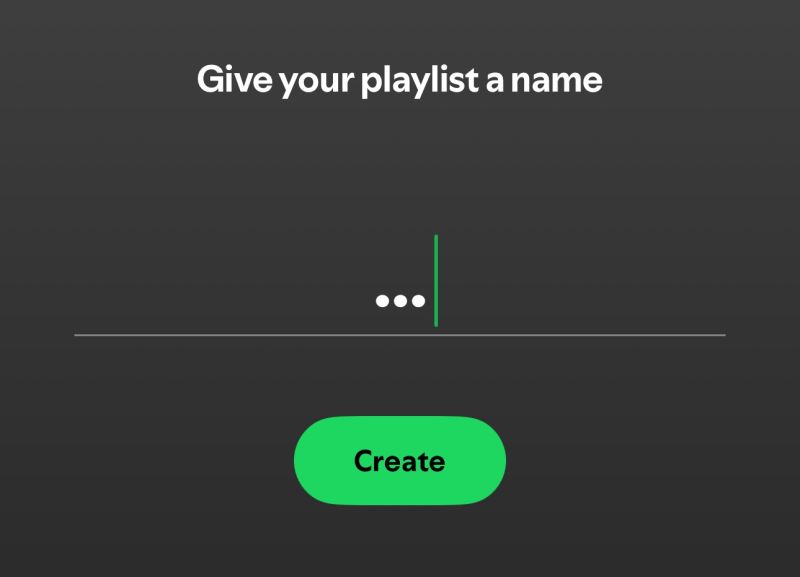

- Social: The playlist is a social ritual, a shared cultural object, embedded with meaning. This is an assemblage of relational aesthetics and shared meaning, not just a “user feature.”

- Aesthetic: The playlist has aesthetic form (curation, sequencing, the musical choices) and a felt experience of being, recognition, joy.

- Politic: The question of who defines value, meaning, and purpose in our digital systems is deeply political. The “design goals” don’t just serve users—they reproduce ideological structures.

Josh’s son’s playlist is an assemblage:

- A social act of identity expression

- An aesthetic structure that signals belonging

- A political alternative to passive algorithmic consumption

- A recursive system of feedback and adaptation

- A space of worlding—a shared symbolic micro-universe

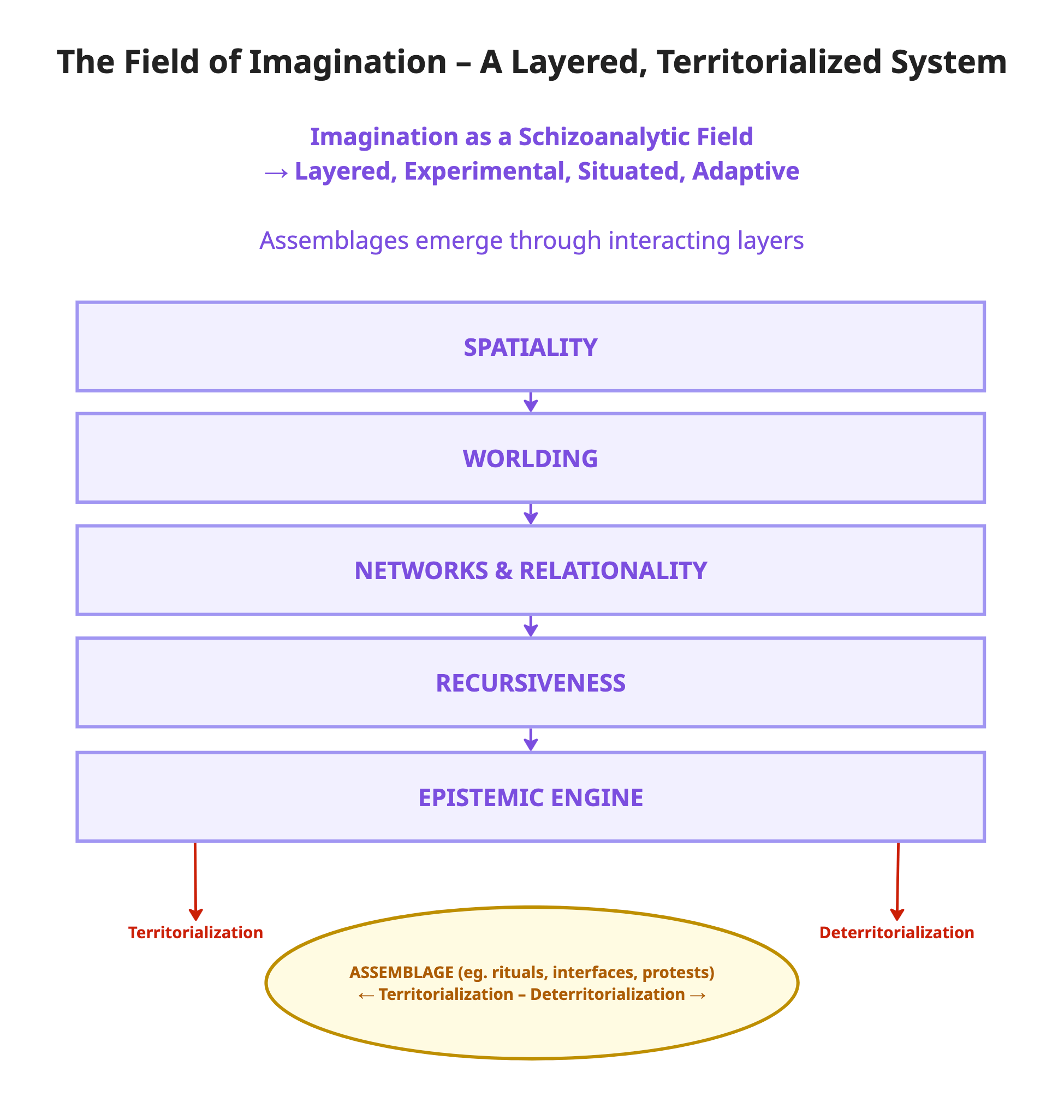

And it exists within the field of imagination, a hallucinatory layer where meaning isn’t consumed, but crafted.

There’s also a political layer at the level of the “users”: what happens when people resist, reinterpret, or remake the meaning of a space?

In Deleuzian terms, this is deterritorialization and reterritorialization in action: The users un-code a capitalist music streaming service and reterritorialize it as a ritual of care, memory, and friendship.

- Josh’s son and his friends turn Spotify—a platform designed to recommend and passively consume stream music—into a site of co-authorship and identity construction.

- This is a micropolitical act: they claim a feature and imbue it with values not intended by the designers.

- These are world-building acts performed within an existing system, but, potentially, against its primary logic.

And because I think the political aspect is often misunderstood, the politic dimension in the trioptic design framework attempt to frame design as a mechanism of power and desire (Foucault, Deleuze)—not just as a response to problems, but as a practice of subjectivation, normalization, resistance, and creative emergence.

Whereas the aesthetic aspect is often overlooked and confused as a surface-layer shallow understanding, the aesthetic dimension in the framework frames design as a sensorial and symbolic force—one that shapes perception, encodes ideology, mediates affect, and participates in constructing the very conditions of meaning, belonging, and agency. It is also recursive, as every aesthetic choice reconfigures not only what is seen or felt, but what can be imagined, expressed, and re-made in the future.

| Feature/Focus | User-Centered Design | Trioptic Design |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Perspective | The individual user | Society, culture, systems |

| Scope | Interaction, usability, satisfaction | Meaning-making, world-shaping, futuring |

| Ontological Basis | Human-centric, often individualistic | Flat ontology (human + non-human actors) |

| Ethical Framing | “Design for the user” | “Design with/in systems, toward desired futures” |

| Temporal Focus | Short-to-mid term | Long-term consequences and possibilities |

| Design Method | Research > Define > Ideate > Test | Compose > Iterate > World > Steward |

So, to summarise in a sort of mini-manifesto, the trioptic design aims to address:

- Design is Never Neutral

- Design is Trioptic

- Design is Imagination in Action (and imagination is a hallucinatory field)

- Design is Spatial, Situated, and Recursive

- Design works in entanglements

- Design Operates on Flat Ontologies

- Design Deterritorializes and Reterritorializes

- Design is an Epistemic Engine

- Designers are Stewards of Assemblages

- Design is a World-building (Political) Act

If you're interested in exploring more, here are some of the theoretical foundations behind the trioptic design approach:

| Thinker | Contribution |

|---|---|

| Tony Fry | Design as futuring and politics, redirective practice |

| Jacques Rancière | Politics of aesthetics, redistribution of the sensible |

| Victor Margolin | Design as political engagement |

| Christo Sims | Design as prescription, publicization, and proposition |

| Deleuze & Guattari | Assemblages, schizoanalysis, territorialization/deterritorialization |

| Haraway, Ingold, Latour, DeLanda | Worlding, relational agency, situated imagination |

| Foucault, Lefort | The political vs. institutional politics |

Designing for AI: new challenges are old challenges

I've recently came across Luke Wroblewski's post, in which he shares his notes of a conference on “designing AI products”.

In his AI Speaker Series presentation at Sutter Hill Ventures, Henry Modisett, Head of Design at Perplexity, shared insights on designing AI products and the evolving role of designers in this new landscape. Here's my notes from his talk

Unfortunately, I did not watch the conference because no recording is available, so please let me know if I misunderstood something on limited information.

It's not the first time that I come across the idea that the challenges brought by AI are particularly novel or difficult. I find quite amusing the idea that anything is new about the challenge of designing for AI –Game design has been around for a while and has had very transposable challenges– or that projects start without knowing if they are technically feasible.

Although the speaker does mention Game design, the framing is still around the novelty of the challenges.

Also, regarding this point:

Product mechanics (how it works) matter more than UI aesthetics. This comes from game design thinking: mechanics > dynamics > aesthetics

In (good) game design, aesthetics reveals game mechanics to players. And aesthetics do shape game mechanics. The missing part here is the story: beyond game mechanics, there is a recursive relationship between aesthetics, mechanics, the story. Meaningful affordances to the player on how to progress.

Therefore, I think it is interesting (and important, perhaps) when designing for AI, to ask what’s the point of it? What the message (politics)? For what outcomes and to whom (social)?

That is the story. And this shapes its aesthetic.

I know this is counter-intuitive in a world where every AI company wants to make a you-can-do-everything-simply-ask-app, but again if we look at game design, we can see that:

- This is not inevitable, all games are not open-world with 1 trillion sub-sub-quests and activities but no stories. One could argue that the best games are quite the opposite.

- Even in (good) open-world games, like say GTA, there is a story and a sense of progression. Yes, the game lets you do countless things, but taking that as the core characteristic of the game is totally missing the point. The open-world is an excuse to tell a story –in GTA, a critique of society through parody of realness– it is an aesthetic choice which allows certain mechanics.

Thanks for reading!

Kevin from Design & Critical Thinking.

References

- Carl DiSalvo, Design and Prefigurative Politics, in The Journal of Design Strategies https://drive.google.com/file/d/1TK3z-8U0ThHU-jPRRgBCSj6nTY3yjfwR/view?usp=sharing

- Tony Fry, Design as Politics (Berg Publishers, 2011) https://drive.google.com/file/d/15z2WM6ysFYkT_qGP42YgUZmBjvqfINbZ/view?usp=sharing

Discussion