Hi, Kevin here.

I find very interesting, in many ways, the current atmosphere in (our?) society. And I'm not only thinking of the overrepresented discussions around artificial intelligence. In my informed view, AI is not (just) a technical "innovation" or "revolution" proposition anymore (if any), but a socio-political proposition that fits a broader transition, motivated by social and geopolitical dynamics, but also climate change.

What I would like to explore here are some vectors of this broader landscape. I recently came across a very interesting thesis that, conversely, fits other relevant signals: that our global economic system, namely liberal capitalism, is transitioning towards something different as a regime.

How is this useful to design, one might ask? I'll come back to this later, but to keep it short, design operates mainly (not only) within the confines of what is perceived as "good," "desirable," and "valuable." And we can see how this change, which has already taken form, is shaping design practices and designers' own perception of what and how they are doing design.

From liberal to mercantile capitalism

Our economy isn't a monolithic and immutable thing, but rather a dynamic and evolving system. Arnaud Orain, a French economist and historian who recently published “Le monde confisqué: Essai sur le capitalisme de la finitude (XVIᵉ - XXIᵉ siècle)” (“The Confiscated World: Essay on the Capitalism of Finitude (16th - 21st Century)”), proposes that we are heading toward more than just an iteration of our current neoliberal capitalism. His thesis, which corroborates many vectors of change observed by other economists, is that the very rules of the game are changing: we are moving away from a liberal capitalism to what Orain calls "Capitalism of the Finitude."

To understand its significance, we have to come back to the main characteristics that constitute the system we have experienced since the end of industrialization: liberal capitalism.

As the Arnaud Gantier, who interviewed Arnaud Orain, explains:

[Under liberal capitalism] parties of the left and right that take power share quite a few values: market economy, competition, free trade, and facilitating access to private property. The main economic disagreement that remains [between the left and the right] is defining a more or less important role for the state in the economy.

To illustrate this, the opposition is between social programs—for example, housing allowances or building social housing—or tax breaks for construction.

This is the type of opposition that has dominated economic debates in Western countries since at least 1945.

But what Orain points out is that before that period of time, our world was governed by a capitalism that was not liberal, which did not care about competition, free trade, or individual freedoms. Because in an imparialist and expansionist world, the purpose of capitalism was to enable states to be more powerful than their neighbors. And we see today many superpowers moving towards a more explicit form of imparial powers.

Obviously we see this with Russia. China’s New Silk Roads also have this dimension, with the construction or rehabilitation of infrastructure. There are actors, for example in Pakistan, who consider the port of Gwadar to be a new East India Company, a new form of colonization being put in place by Chinese firms.

We are obviously thinking of the United States of America, with desires for acquisition or protectorate over Greenland, and the Panama Canal returning to the U.S. sphere. That is just one sign.

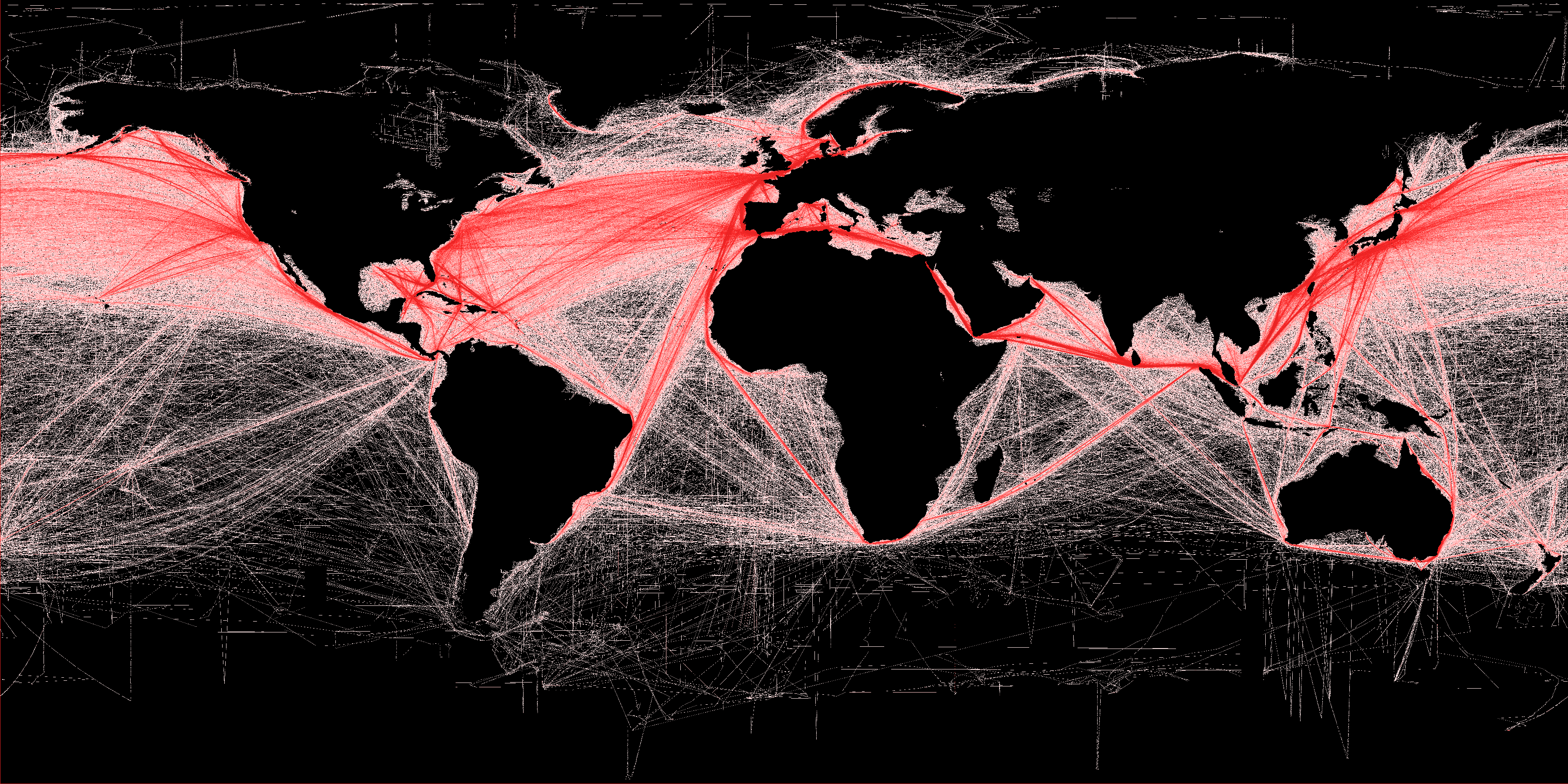

But there are many others, notably all the limits to the freedom of trade at sea, which is a truly central idea because almost everything we consume daily is transported over thousands of kilometers across the oceans.

But why talk about mercantile capitalism then? The interesting part that Gantier highlights is the role of merchants and traders in the history of capitalism, but overall in the history of societies and their politics—better exemplified nowadays by the influence of billionaires on governments.

[In the 17th and 18th centuries] the planters were the farmers in the French colonies who used enslaved labor to produce sugarcane, [...] were powerful, armed, and sold highly valued products.

But in reality the ones who controlled this economy were not the planters themselves, but the merchants and traders, who were indispensable for transporting both enslaved people and sugar.

They could choose which planter or producer would be able to sell their goods and thus become rich. So they held the power.

Interestingly, the history of our liberal period, which sees merchants and companies as peaceful organizations, trade as a way to avoid wars, and capitalism as a way to enrich workers, does not provide the necessary model to understand the effects that these merchants and their companies have, whether the emancipation of workers they can sometimes allow or, on the contrary, their central role in colonization and slavery.

This view of history is too partial and is fundamentally contradicted by the present. We can start with the most radical examples, like private military companies. For example, the American firm Constellis, formerly Blackwater, or the Wagner militia, which have grown in importance in recent years.

What they do is employ soldiers under contract. They are private armies, and in the last ten years they have been deployed all over the world, whether in Iraq, Yemen, Israel, Mali, Ukraine, and they often leave behind crimes against humanity.

We also see this in high-intensity conflicts, for example in Ukraine, which reminds us that wars are won in factories, that is, by companies. It is no coincidence that GDP was invented during World War II. It was an indicator to measure production capacity. Who can produce the most missiles, tanks, fuel, food, clothing, shoes.

So controlling industrial capacities, controlling companies, merchants, traders, this entire world, is not an abstract question. It is a major power issue.

What's changing might be better encapsulated in the notion of company-state: companies that are both merchants and possess sovereign powers. This was true of many companies back in the 17th and 18th centuries, who could buy and sell things, mint money, administer justice, and raise armies, and it is becoming more apparent that, today, many companies are in such a position. These companies are sometimes aligned with the public power, and sometimes in competition with it. For these reasons, big modern merchants depend less on free trade than others, and we see this clearly in their media.

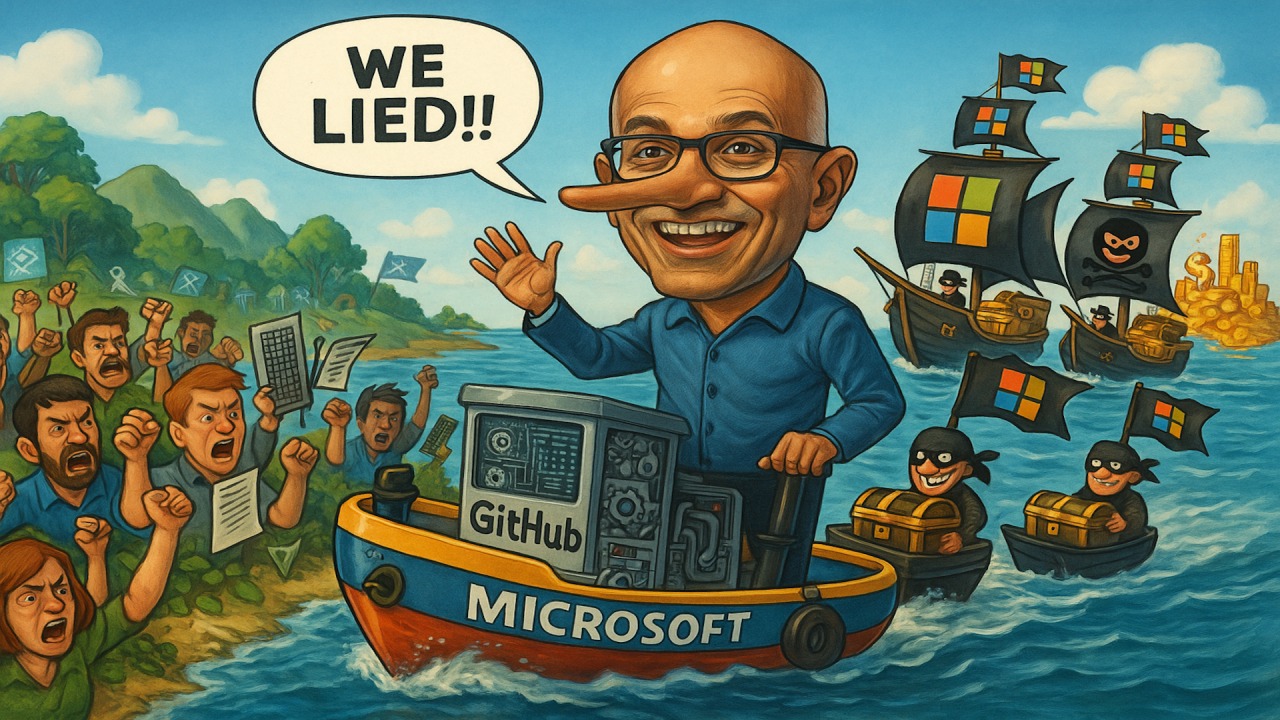

In an adjacent case, I find interesting the recent takeover by a techno-corporate power of the digital open-source community, marking here again the decline of liberal ideals, and the colonisation and exploitation of yet another form of territory.

Another interesting change is that, for long, liberal capitalism worked mainly on the idea of seduction and promises of improved living conditions. Mercantile capitalism does not bother with promises of enrichment for all in order to expand.

What Orain is saying here is simply that for socialists, the more violent capitalism becomes, the less it relies on seduction to expand, and the easier it becomes to present socialism as a positive idea.

Today many [French] people think they can improve their living conditions outside union struggles. For them unionism is even hidering the improvement of their personal situation. But that can change quickly.

In a mercantilist capitalism where companies are increasingly monopolistic, the workforce has no real alternatives. There is not one employer really better than another when there are very few.

In each sector you do not have a choice among a dozen companies. It is either one or the other. They probably talk to each other and align their working conditions.

In such conditions, unionism and socialism appear as logical choices to improve one’s condition.

Finally, Arnaud Gantier concludes with some very interesting points.

First, we should acknowledge the death of neoliberalism. Many still operate on obsolete ideas of a neoliberal world declining, among which are most traditional political parties. Ideas that are no longer promoted by the parties we see rising in the polls (in Europe). For instance, many far-right parties rising in popularity are in fact mercantilist, notably because they display ideas of labor exploitation, and they consider the grandeur of the nation to come before the rights of those who live and work there. This model of capitalism no longer rests on the existence of a large middle-class and social policies.

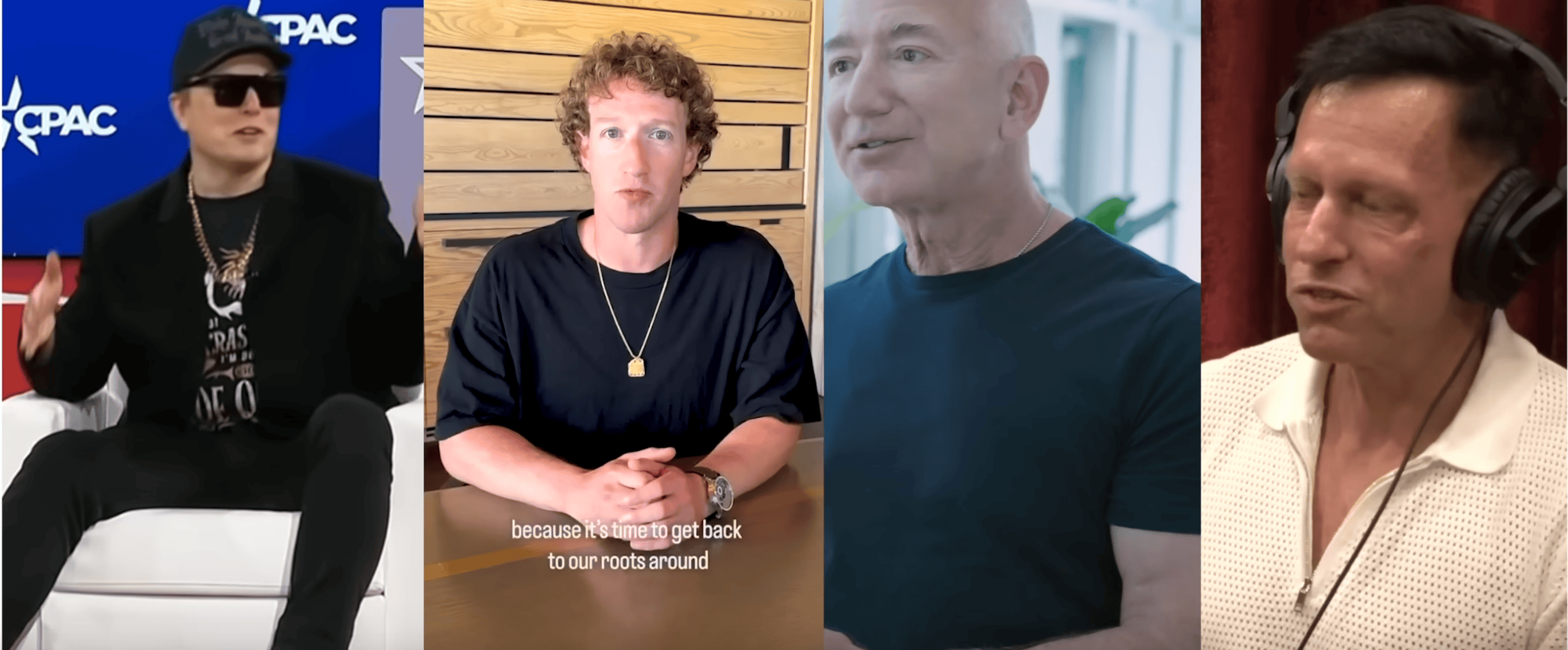

Second, the role of the most visible representatives of these neo-mercantile companies, the billionaires, is a consequence of actors no longer bound by the same rules. They all own media, and their political actions go far beyond humanitarian actions, making them obvious political enemies. Here, neo-mercantilism describes a capitalism, that is, private ownership of the means of production dominated by merchants, and with it the decline in influence of the traditional economist-intellectuals that marked neoliberalism.

Finally, climate change plays an important role in this economic transition by adding a compounding factor in precipitating this neo-mercantilism, by adding social and resource pressures –hence the term "capitalism of the finitude" coined by Arnaud Orain.

So, in summary, Orain's thesis can be summed up as such: Liberal capitalism is giving way to a neo-mercantilist “capitalism of finitude” where state power, monopolies, logistics chokepoints, and “company-states” dominate, and allegiance becomes a central political problem.

This transition is marked by key signals/components:

- Re-imperialization of great powers and growing limits to “freedom of the seas.”

- Merchants as political actors, historically and today, via debt, logistics control, and media ownership.

- Militarization of enterprise, including PMCs; war as industrial capacity.

- Shipping giants under state pressure and possible self-militarization.

- Allegiance problem of multinationals through opaque corporate architectures.

- Company-states in tech with sovereign attributes (space, satellite, platforms).

- Divergent capitalist blocs: exporters of branded goods prefer free trade; defense/logistics fit mercantilism; media lines mirror owners.

- Return of monopoly capitalism, making nationalization and unionization logically salient again.

- China’s model of national champions and enforced corporate allegiance, with systemic fragilities.

- Political realignment in Europe: neoliberalism fades; the far right is mercantilist rather than liberal; the left’s anti-billionaire stance gains traction.

This is great and all, but why should designers care?

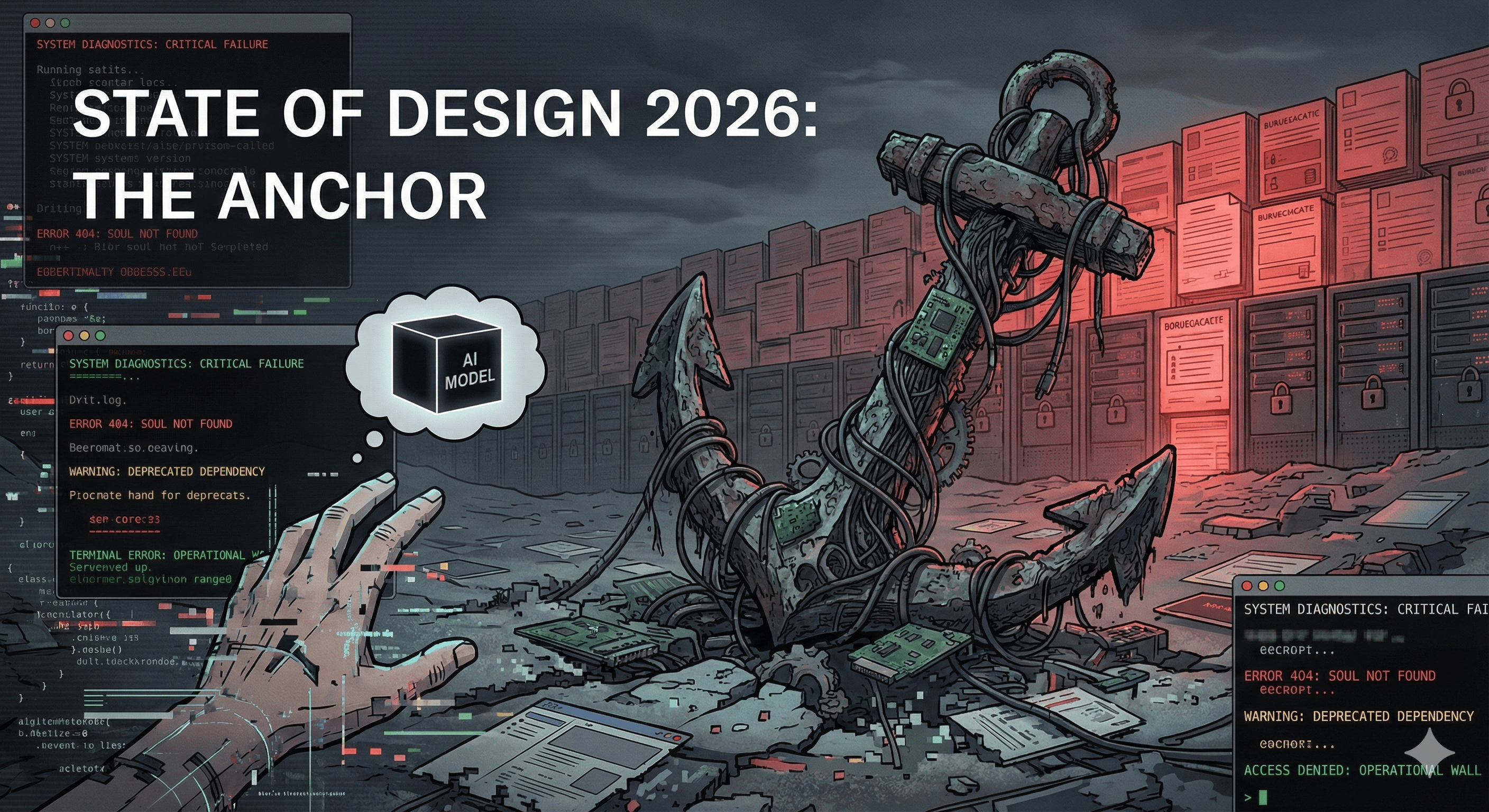

Well, modern design practices have been mainly in service of a liberal capitalism. The modern idea of liberal arts and applied arts, which gave birth to most current Western (globalized) design movements, and the history of neoliberalism and its means of production have always been tightly coupled. When Dieter Rams talks about "good design," he does it in a neoliberal globalized worldview, built on the shoulders of prior movements such as Bauhaus. That's actually one of the main criticisms of Viktor Papanek.

Today's UX/CX, product, and service design are predicated on the rules of a liberal regime. What is defined as "good design" and the means through which it is valued (e.g., customer satisfaction, conversion rate, user's autonomy and consent, etc.) and operated will likely become obsolete as the system's conditions mutate.

If capitalism is indeed pivoting from a liberal, competition-led order to a mercantile one organized around state (firm blocs, choke-points, and extraction), then digital design’s mandate and its yardsticks shift with it:

- Value theory: Liberal UX treated people as choosing users; the mercantile turn will likely treat them as managed subjects inside vertical stacks (identity, payments, logistics, compute). “Good” becomes what secures allegiance, reduces contestation, and locks channels.

- The real client: Expect more briefs from hybrids of state and “gatekeeper” firms. “Good design” will likely be redefined in law, not just taste.

- Metrics mutate: The center of gravity will likely move from conversion and NPS to contestability, compliance, and provenance.

If you think this connects well with the notion of enshittification and techno-feudalism, this is no accident.

Anyway, if the debate nowadays revolves mainly around the impacts AI has/will have on liberal professions (such as artists and designers), we might be very well myopic to the very context in which this is unfolding.

The error of many designers is to treat it as yet another technical or alignment challenge to solve (supposedly between user needs and a technical system), while failing to recognize that AI is not just another technology, it is a catalyst to unfold certain political ideals, which in turn unfold a certain aesthetic (see trioptic design).

Finitude, violence, AI, and fascism

I would like now to connect what we just explored with another highly compatible thesis: the idea that Platform capitalism (that is, a capitalism dominated by digital platforms, themselves owned by merchants) enabled a new form of fascism, what Bertram Gross calls “Friendly Fascism”.

Platform capitalism already happened, and likely enabled the transition we see towards neo-mercantilism, as platform ownership reorganizes power: labor is “platformized,” markets become gatekept, and public rules increasingly run through "private UX"—that is, interfaces and interactions that govern quasi-public life (speech, trade, work, ID, mobility), but are designed, owned, and enforced by private companies rather than public law. See how this description fits the notion of company-states we just discussed?

In his work "The New Aesthetics of Fascism", Ben Hoerman, who draws from B. Gross work and many others, explains how fascism has been “redesigned” for platform capitalism into a friendlier, quieter form: it advances through technocratic bureaucracy, corporate control, culture-war monetization, and AI-driven aestheticization that makes cruelty look normal, pretty, or ironic so people won’t resist it.

From The New Aesthetics of Fascism — founder-cult montage as political influence.

It highlights several key signals/components:

- Form factor shift: from overt militarism to technocratic bureaucracy, corporate control, and manufactured media staging.

- Culture-war governance: class conflict is displaced by culture war, algorithmically amplified; soft authoritarianism hollows institutions while the shell remains.

- Bureaucratic violence: repression by policy stack: union-busting, surveillance, deregulation, and paperwork that punishes instead of guns.

- Corporate neofuturism: minimal, cold, speed-obsessed tech aesthetics plus founder cults and deep ties to the military-industrial complex.

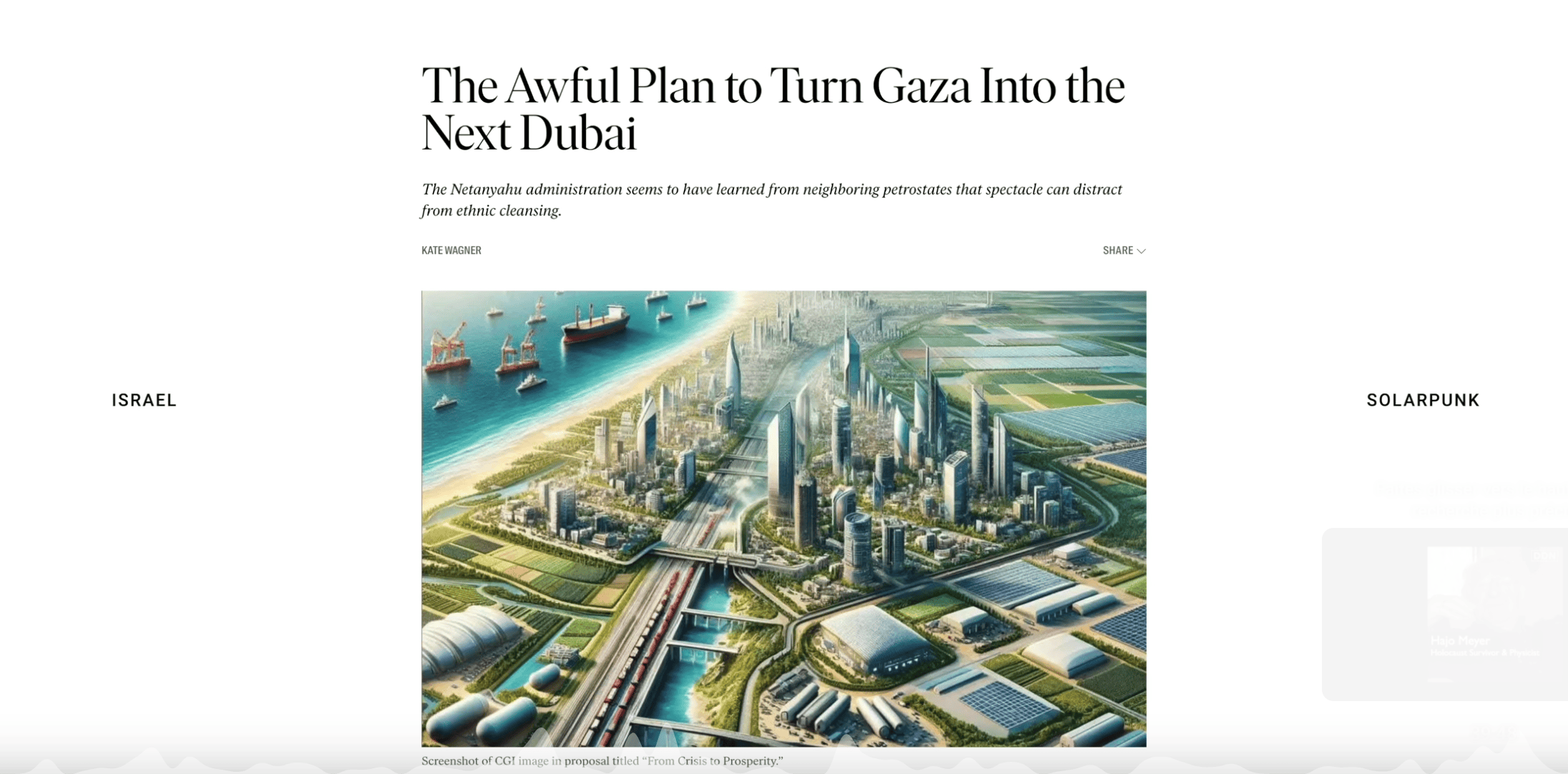

- Eco-fascist drift of solarpunk: harmony-with-nature visuals repurposed to whitewash regimes and sell exclusionary nationalism.

- Everything as content: politics becomes spectacle for mass consumption; “nothing is obscene anymore” normalizes the previously unthinkable.

- Irony pipeline: edgy sarcasm and memes trivialize harm and provide a shield against critique: “just joking.”

- AI slop and deepfakes: endless reproduction dilutes meaning; deepfakes become an oppression tool (noted as overwhelmingly pornographic in surveys).

- Cute-wash: moe/anime aesthetics soften or trivialize violent or exclusionary messages, making “friendly” fascism literal.

- Edgelord/incel iconography: dehumanizing caricatures and eugenic “attractiveness metrics” repackage hierarchy and cruelty.

- Oligarchic alignment: private firms and unelected elites increasingly steer policy; corporations enable the drift so long as profits are protected.

- Desensitization + cynicism: constant spectacle and ironic remixing create meaninglessness, eroding shame and consequences for fascist rhetoric.

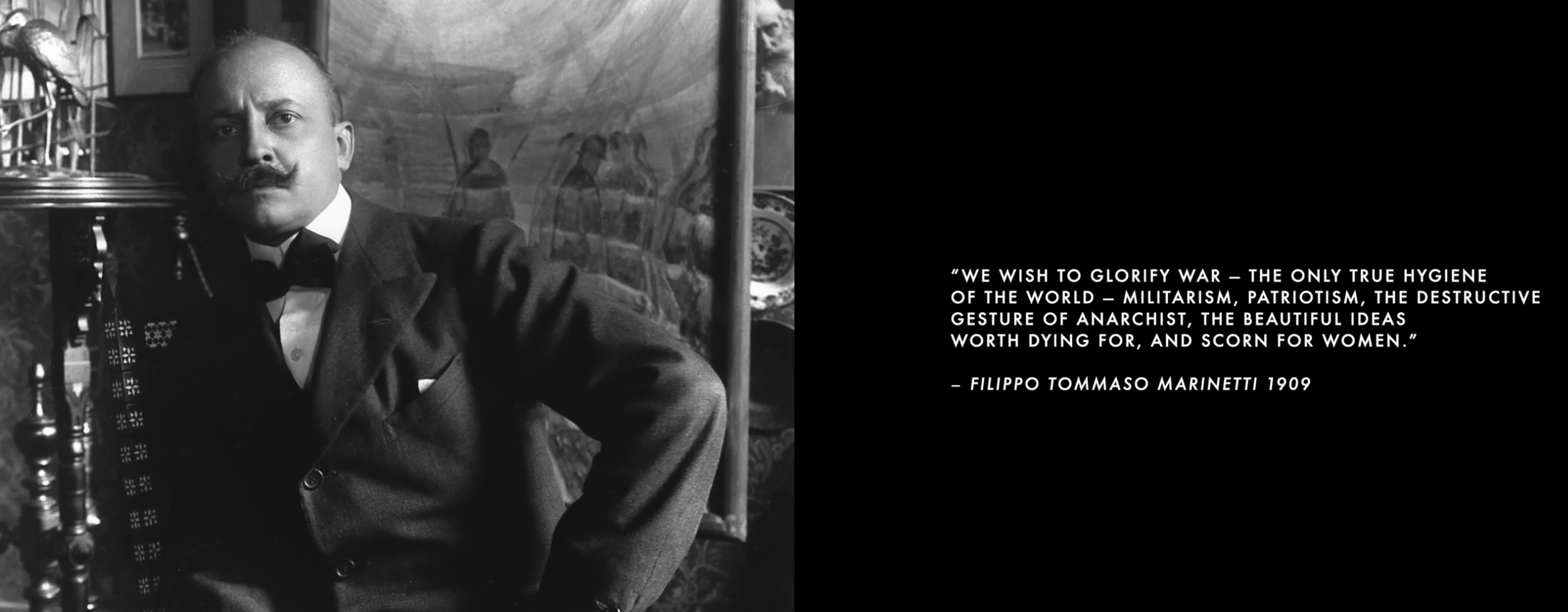

From The New Aesthetics of Fascism — Futurist quote glorifying war and scorning women, rooting today’s style politics in earlier manifestos.

Difficult to not see many convergence points with neo-mercantilism indeed. Although fascism is not an intrinsic feature of mercantile capitalism, its imperialist feature and allegiance politics (here mainly expressed through culture war as a means of control) make the perfect conditions for fascism to grow.

From The New Aesthetics of Fascism — examples of AI “cute-washing” that normalises coercive state power and recasts militarism as friendly or heroic.

Also, the idea of a pervasive violence that comes with this new system is very well encapsulated in this sentence:

nothing is obscene anymore.

This new aesthetic, facilitated by AI, is about making the violence acceptable, the obscene beautiful, and the absurd funny or sarcastic. Because then, you won't do anything about it.

Memes and AI generated images turn everything into irony, in a kind of meta-self-fulfilling realization of the now-famous illustration of a cartoon character sitting in a room on fire who tells the audience, “This is fine.” Except here the character knows they are in an illustration, as an allegory to inaction in times of crisis, but diverted and subdued from its original meaning. In a cynical way, the scene becomes, then, purely performative: it has become the very thing it was denouncing.

If climate change adds ecological, social, and economic pressure, it is turned not into a force for change (as many hoped at some point) but into another form of control —whether it is believed to be real or not isn't even remotely the point.

Nothing escapes the cultural reappropiation of this new engine: solarpunk and Afrofuturism have been subdued and repurposed to serve ethnic exclusionism, eugenist exceptionalism, and social hierarchies. Corporate minimalism signals purity. Christian symbolism, echoing neo-Christian nationalism and fundamentalism, has replaced Nazi mysticism.

Beyond the very finitude of our world, exemplified by the effects of climate change, the system behind this aesthetic is, itself, finite. Much like the architecture of fascist regimes of the 1930s, there is an order, a hierarchy, and the intent to find perfection through its minimalist completeness (purity). It's made to erase any sense of personality and diversity. It is huge and yet enclosed. Furthermore, it projects the grandeur of the nation while being inhuman to its visitor.

Examples of Nazi architecture — authoritarian grandeur as closed, finite aesthetics, and classical scale as a tool of power.

Why should designers care?

This “new” fascism does not only live in images; it lives in decisions. It lives in roadmaps, risk registers, taxonomies, policy playbooks, moderation criteria, brand charters, data schemas, model prompts, vendor contracts, and KPIs. These are design artifacts. They decide what is visible, sayable, and countable before any interface is drawn. Designers operate inside this assemblage. We convene the workshops, write the definitions, choose the thresholds, and specify the workflows that become everyday governance. Because aesthetics is the materialization of these choices under political constraint, the look is not separable from the order that produced it. The “friendly” tone is an artifact of process, not just taste.

The likely impact is a rotation of purpose. Where liberal practice prized optionality and consent, briefs will increasingly ask for stability, risk containment, and allegiance. Decision artifacts will be evaluated by their throughput and their capacity to suppress volatility. Designers will be pulled into culture-war administration: incident playbooks, trust and safety roll-ups, and “brand suitability” rules that quietly redefine who may speak and on what terms. Metrics will follow. Fewer teams will be rewarded for enabling criticism or organizing; more will be rewarded for reducing appeal rates and moving enforcement faster. The profession’s autonomy will narrow as state-platform blocs set the frame and as procurement translates political priorities into non-negotiable requirements. Aesthetic conventions will harden around this: streamlined authority, hygienic calm, the absence of trace or conflict. It will feel professional. It will also be political.

Counter-strategy begins where decisions begin. Treat every key artifact as a site of resistance. In policy and taxonomy, name harms and externalities explicitly; make provenance, ownership, funding, and edit history first-class fields. Use aesthetics to witness rather than to launder: show cost, labor, and risk at the level of the artifact.

The Trioptic design approach follows from this: socially, return people from spectatorship to participation by designing recourse and assembly into the system; aesthetically, break the spell by materializing what the order tries to hide; politically, write enforceable rights into specifications so that power meets constraints upstream.

New Space, Anti-science, and Astrocapitalism

Finally, this is the last piece of the puzzle. In this interview, Arnaud Saint-Martin, a French sociologist of sciences specializing in the space domain, discusses the notion of astrocapitalism he developed in his recent book “Les astrocapitalistes: Conquérir, coloniser, exploiter” ("Astrocapitalists: Conquer, colonize, exploit").

The reason I connect “Astrocapitalism” with our discussion is because it is the extension of platform capitalism and company-state power (mercantile capitalism) into orbital space: private mega-constellations and launch providers, aligned with national projects, enclose orbital commons, privatize gains, socialize risks, and normalize minimal regulation through seductive “New Space” visions.

Its relevant key signals/components discussed during the interview are:

- Vision work as ideology. Futures are framed as desirable and inevitable; “New Space” functions as a political project, not just tech progress.

- State ↔ firm fusion. Start-up rhetoric “transforms the state”; governments adopt the New Space lexicon and build national champions.

- Orbital enclosure & massification. Mega-constellations (e.g., Starlink) crowd orbits and frequencies; a “Fordism in space” logic scales rapidly.

- Platformization in orbit. Closed user-bases, lock-in, and sovereign constellations (Starlink/Kuiper/Guowang; EU IRIS²) mirror platform capitalism’s walled gardens.

- Regulatory minimalism. Talk of “space traffic management” often displaces stronger planning/limits; current rules leave externalities unpriced.

- Privatize gains, socialize risks. Publics carry debris, spectrum, security, and environmental burdens; firms capture rents.

- Hegemonic geopolitics. U.S. leadership is staged as “get in line” at venues like the IAC; space power is openly strategic.

- European mimicry + “sovereign cloud/space.” Large data-center and “sovereign” infrastructure pushes reveal energy/water/material loads and security theater.

Conclusion

It is important to recognize what is happening, this reorganization of power, and take a step back from narrow discussions that may give the illusion that these changes and how they unfold are about technical or alignment challenges to be solved. However, we should not focus only on the negative impacts and ramifications of this transition.

The three theses are, in fact, three angles on the same movement. Liberal competition yields to mercantile blocs that secure chokepoints and allegiance. The obscene is normalized by an aesthetic that folds cruelty into paperwork, humor, and spectacle until nothing bites. The frontier shifts upward into orbit, where platforms and states co-manage enclosure. None of this sits outside design. It is organized through design. Aesthetics is the materialization of decisions under political constraint. The message cannot be separated from the space that produced it.

There are opportunities: the transition does not only remove, it also reveals where to intervene and with whom. It reminds us that designers are makers, and makers do not have to exist only by serving someone else’s power, money, or agenda. The artifacts we make are set conditions for others; they are means for change.

There is another route that matters, and it belongs to culture. Artifacts of fascist regimes present themselves as total. They project grandeur yet are closed and finite: their power is to exhaust the imagination of difference. Designers can counter by making room for plurality by adding diversity and ambiguity on purpose, not as noise but as a practice.

The twentieth-century lesson from music and art is useful here: scenes in the seventies, eighties, and nineties grew by selecting, curating, sampling, decomposing, and recomposing. They created meaning by recombination and citation rather than by a single heroic line. Similarly, we can compose systems that are forkable, repairable, and open to local authorship. We can create patterns that permit remix, rather than forbid it, that curate dissent inside the work so that difference is not an afterthought but a condition of use.

The conclusion is not that design should save the world. It is smaller and harder. Design should accept that it already governs parts of it. If that is true, our task is to make that governance legible, contestable, and open to correction. To make alternatives when the market offers only enclosure. The future will be designed all the same: the choice is whether we design it as if people and worlds will have to live inside it, and whether we leave enough opportunities for others to participate and make it their own.

Thanks for reading!

Kevin from Design & Critical Thinking.

Discussion